By Louise Taggart, Threat Intelligence Analyst

This blog is based on a presentation originally given by Louise Taggart at the Luxembourg Cyber and Threat Intelligence Summit in October 2022.

Cyber threat intelligence has undoubtedly become a much more familiar concept over the course of recent years, driven in part by frameworks such as CBEST in the UK, TIBER in Europe, CORIE in Australia and NIST in the United States, as well as emphasis in ISO 27002 and wider trends such as shifts in ways of working.

Against that background, organisations are increasingly recognising the value that strategic intelligence can add, alongside technical and operational intelligence. This blog will explore the context of strategic threat intelligence, the insights it can provide, and the real-world impact it can have in a business context from the perspective of the PwC Threat intelligence team.

What do we mean by ‘strategic’?

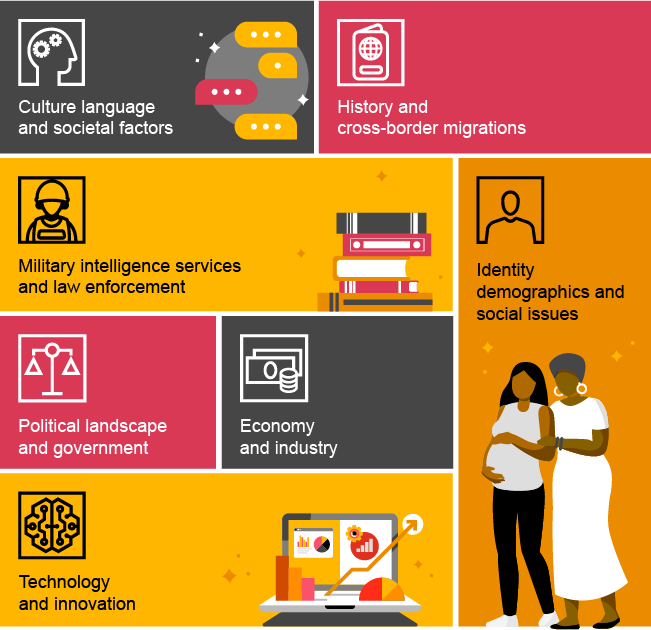

Organisations which may have focused more heavily on tactical and operational intelligence are increasingly setting their sights on how they can integrate strategic intelligence more effectively. However, this can sometimes be hampered by the fact that it can be difficult to define exactly what we mean by the term itself. With much of the theory behind Cyber Threat Intelligence originally being derived from the military community, definitions can consequently often have a military or policy angle to them. Additionally, as something of an umbrella term, strategic intelligence can cover a wide variety of factors including, for example:

- Culture, language, and societal factors;

- History and cross-border migrations;

- Military, intelligence services, and law enforcement;

- Identity, demographics, and social issues;

- Economy and industry;

- Political landscape and government; and,

- Technology and innovation.

Drilling down even further, the term can span country-specific factors (such as border conflicts, respect for rule of law, or history of social unrest); sector-specific factors (such as the level of government involvement, criticality of an industry, or global commodity prices); or even more granular at an organisational level (such as M&A activity, political exposure, or joint ventures with state-owned enterprises). All of these individual factors - and more - can influence the cyber threat landscape.

For the second half of 2023, for example, we are tracking a number of geopolitical events which could shape the cyber threat landscape, such as multilateral summits and elections scheduled to be held. More broadly, other trends we monitor as they emerge include uses of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), nation states’ development and investment strategies, and the evolution of regional alliances.

Challenges

The complexity and richness of this strategic context can, therefore, make it more difficult to convey the value that it can add because in itself it can be difficult to pin down exactly what we mean. This is particularly true when we look at strategic intelligence in the wider context of three traditional ‘pillars’ within the umbrella term of cyber threat intelligence and the audiences they are intended for.

However, within the context of these three pillars, it also becomes obvious that - as well as being more multifaceted - strategic intelligence can also be more difficult to ingest; one more factor as to why its value can be more difficult to articulate to a technical audience.

Benefits and use cases

Despite some of these challenges, however, strategic analysis can add real value, both in terms of intelligence production as well as wider business considerations. Below, we examine some real-world applications where strategic analysis can bring real benefits.

Threat actor activity - White Tur

White Tur is a threat actor we have tracked since January 2021, with technical details of some of its previous activity previously outlined in a PwC blog1 and presented at SANS Cyber Threat Intelligence Summit 2022.2 Given the threat actor’s apparent very specific geographic targeting of Serbia and Republika Srpska (one of the federal entities comprising Bosnia and Herzegovina), complementary strategic analysis allowed us to explore the wider geopolitical context in which this targeting was occurring, examining the multitude of vested interests in the region, its very complex history and its historic divides over language, borders, religion and identity which still shape aspects of the region today.

Strategic intelligence allows us to move beyond the technical details of a threat actor’s activity towards understanding what the motives driving this activity might be in the first place, allowing for insight into possible further targets of interest - and ultimately the defensive mechanisms we can put in place to guard against future attacks.

It is also important to remember the human aspect of the adversary. Threat actors, particularly those motivated by espionage, have their own goals informed by long-term priorities - often aligned to the wider strategic, geopolitical context in which they are operating.

Supporting market expansion

For a multitude of reasons, organisations - whether public or private - can experience (or suffer from) siloing, whether that be in structure, process or mentality. Most large companies have divisions, or even groups and functions within divisions, that operate in silos.3

For example, information around an organisation exploring expansion into new geographic markets might be deemed market sensitive and therefore not communicated beyond the immediate commercial or risk team. However, depending on the nature of a company’s operations and its expansion plans, this could have a significant impact on its cyber threat profile. For example, an organisation expanding into a new operating location in which there is a high level of state involvement in the economy and where this overlaps with the country’s domestic strategic interests, could find itself the target of intelligence-gathering activities.

When organisations are considering expansion, they will typically conduct assessments for ‘classic’ business and political risk, for example, political stability; rule of law; bribery and corruption; physical safety and security; even natural hazards. Many of these types of threats are, in some ways, easy to align by geographical exposure as they are frequently driven by specific local or national issues, such as socioeconomic tensions or political events.

Undoubtedly, geography can have an effect on an organisation’s cyber threat profile. However, cyber threat considerations do not necessarily fall into the same country-specific silos as other types of operational or business risk, and the cyber threat landscape is not necessarily included as standard within this type of country risk assessment.

However, even with these caveats, the inclusion of the cyber threat landscape can bring additional context to country or market risk assessments. For example, for a client considering expanding its operations into a new location, this could include:

- Examples of previous incidents affecting a particular geography, and their impacts;

- Overlaps between an organisation’s planned market expansion, and known active targeting of sector/geography;

- Profiles of threat actors known to target the country; and,

- Alignment of threat actor activity with real-world events and the evolving geopolitical landscape pertinent to the organisation’s plans.

This type of assessment, briefed to a strategic leadership team looking at expansion opportunities, can help to inform the wider decision-making process. In instances such as this, strategic intelligence can provide greater insight and context into some of the potential risks of entry into new markets, and provide actionable recommendations.

Conclusion

As cyber threat intelligence becomes an increasingly mature discipline and integrated into cyber security operations more broadly, the role that strategic intelligence can play will likely be more greatly recognised and appreciated. By providing answers to questions such as ‘so what’, ‘why’ and ‘what’s next’, strategic intelligence can inform business decisions and provide context to organisational threats.

1 https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/cybersecurity/cyber-threat-intelligence/threat-actor-of-in-tur-est.html

2 https://www.sans.org/presentations/threat-actor-of-in-tur-est-unveiling-balkan-targeting/

3 https://www.strategyand.pwc.com/gx/en/insights/2016/dealing-market-disruption/dealing-with-market-disruption.pdf

Contact us

Global Threat Intelligence, Senior Manager, PwC United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0)20 7212 1912

Global Threat Intelligence Lead Partner, PwC United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0)7725 707360

Contact us

Cyber Threat Operations Lead Partner, PwC United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0)7725 707360