{{item.title}}

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}

Capturing value in the growing energy domain

There’s a fundamental energy challenge—shrinking the world’s carbon footprint while providing reliable, secure, affordable energy. Attempts to address this have unleashed waves of innovation from established players, start-ups and participants from other industries. A domain of growth is taking shape around how we fuel and power our lives.

Sustainability and business performance go hand in hand. Those that get the energy transition right will thrive. Decarbonising traditional operations. Scaling up renewables. Building greener. Operating leaner. The transition is underway. We can help you make every move count—let’s seize the opportunity to supercharge your business.

By changing how your organisation uses energy, you can save money and build resilience—increasing productivity, improving margins and reducing exposure to market swings and global events.

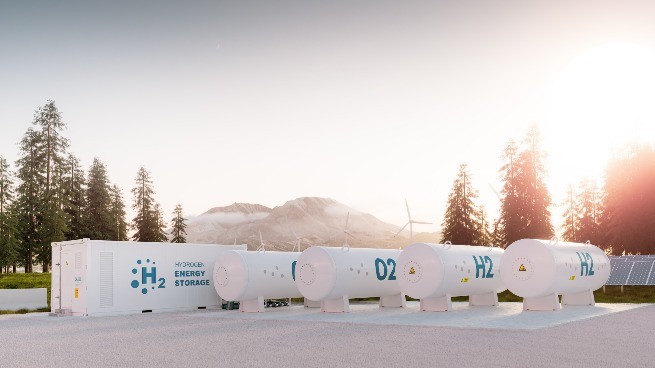

To achieve net zero by 2050, we need to go beyond electricity. We need to embrace alternatives. As sustainable aviation fuels, hydrogen and biofuels become scalable and commercially viable, they will play an essential part in powering the transport of the future.

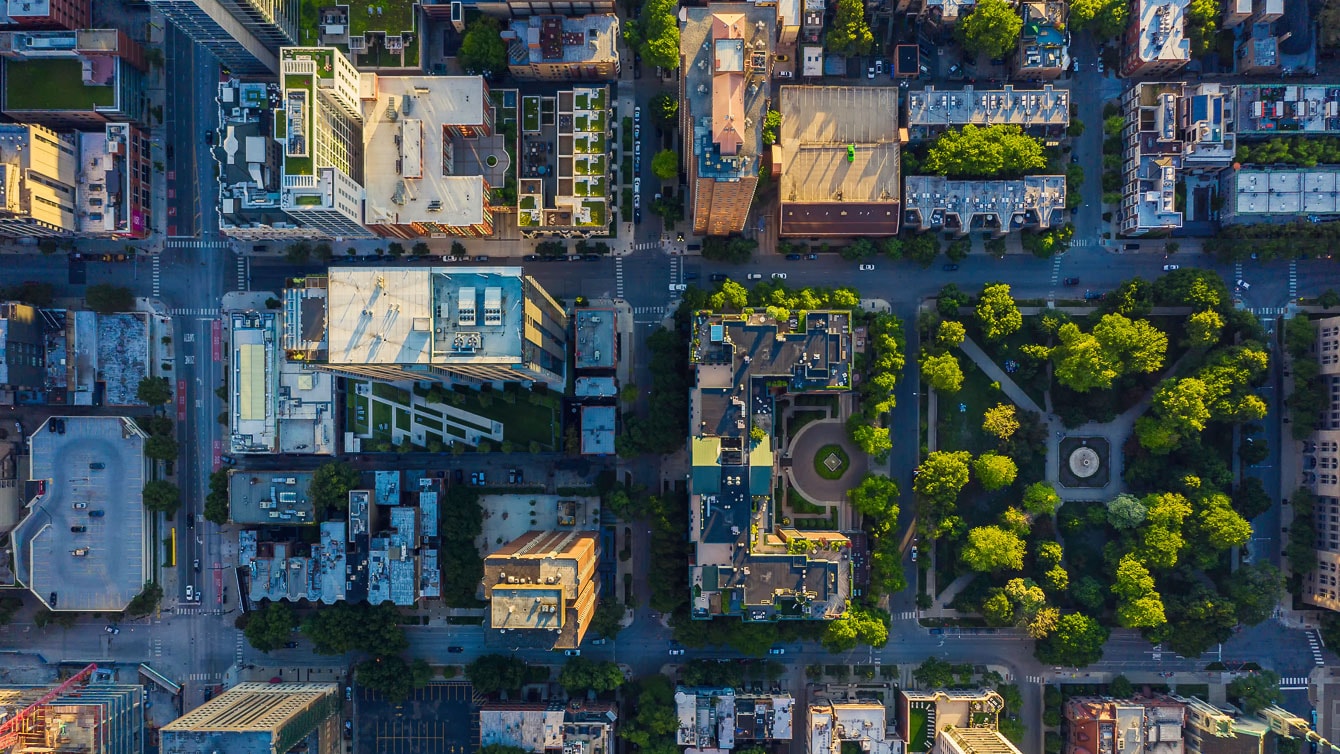

Seventy percent of greenhouse-gas emissions come from energy, industrial activity and buildings. Achieving net zero means transforming our renewable energy and power-grid infrastructure—how we plan, finance, build, operate and decommission.

Decarbonising hard-to-abate sectors is complex—and vital to get right. The chemicals industry must move quickly to embrace green energy—teaming with agriculture and manufacturing, using less hazardous chemicals and adopting low-carbon production methods. We must move to the circular practices that protect our planet.

This is mining’s moment. The demand for critical minerals is skyrocketing. But the sector is under pressure to accelerate to low-carbon mining. Transformation costs can be controlled with targeted investment and reimagined business models. By sustainably extracting the green minerals that will be needed to power our world, the mining industry is not just transforming itself—but becoming the cornerstone of a sustainable future.

Industries are reshaping around fundamental human needs, creating value through collaboration across interconnected domains that now replace traditional value chains.

Successful energy transition will be led by bold organisations. Companies around the world are proving that comprehensive decarbonisation is possible. The transition to cleaner supply and leaner demand is driving innovation and creating new value for businesses and society.

Professor Michael Pollitt - Professor of Business Economics, Cambridge University - shares his insights on the need for global cooperation and innovative technologies to tackle challenges in decarbonization and enhance energy resilience.

Hydrogen may be critical to achieving net zero. Use our online calculator to find out if switching to hydrogen is worth it. Build a first business case analysis and quickly assess your application-specific hydrogen and related electricity requirements.

Get started

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}