In Only the Paranoid Survive, Andy Grove defined an inflection point as “a time in the life of a business when its fundamentals are about to change.” Speaking from hard-won experience, the former Intel CEO went on: “That change can mean an opportunity to rise to new heights. But it may just as likely signal the beginning of the end.” Today, it feels like the world is at such an inflection point. Inflation is rising to the highest level in 40 years. We’re living through greater uncertainty about energy and food supplies than most corporate leaders have experienced during their careers. There is war in Europe. China’s leadership has announced that it intends to supplant the US as the leading technological and military power. The millennial workforce exhibits behavior and beliefs that stand in marked contrast to those of older employees.

Inflection points push corporate leaders into a strategic danger zone. Not only do such moments upend the business assumptions underpinning many existing strategies, but they can also inadvertently yield new strategies that arise from an incoherent reaction to the situation at hand. For example, a media company that borrows to finance the creation of new content for the streaming wars may have to rethink its strategy when suddenly faced with both higher interest rates and inflation-pinched consumers.

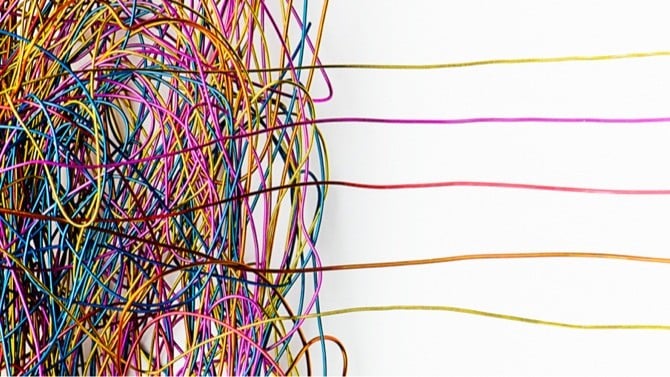

Knee-jerk responses to such challenges can create new problems, and with surprising speed. Before a company’s leaders know it, they have undermined the coherence of their strategy—by which I mean the concentration of effort, resources, and strength where opportunity is greatest or competition is weakest. Strategic coherence requires that policies and actions support one another to this end. Or, at a minimum, do not conflict. In this article, I’ll describe the costs of incoherence, the benefits of focus, the importance of identifying real challenges, and the pitfalls to avoid on the way to strategic coherence.

The strategy null set

If a company says it will cut capital investment and build new facilities, the incoherence is obvious. But if the company expresses ambitions of both growth and a higher return on capital, the incoherence may be masked. Consider this list of priorities generated during a business strategy retreat by the small executive team leading a Fortune 500 company:

- Supply chain and process excellence.

- Improve debt rating (move EBIT-to-interest ratio from 1.2 to 2.0).

- Push return on invested capital above weighted average cost of capital.

- Reverse market share losses with new product offerings with new capabilities.

- Manufacturing technology: double throughput, reduce energy consumption by 25%, reduce emissions by 35%.

- Better branding and image positioning.

- Become the market leader in China for the category.

- Stronger presence in Southeast Europe.

Leaving aside the fact that having eight priorities violates the very meaning of the word, the policies and intents themselves are incoherent. The list contains implied actions that directly contradict one another. Market share losses, debt problems, and low profitability are symptoms of past overinvestment in poor competitive positions. Large investments in new manufacturing technology and expansion in China and Southeast Europe are hard to square with the hoped-for improvements in the income statement and balance sheet. More generally, there is no concentration of effort—no focus—and this contravenes the fundamental principle of strategy. It is all too easy to create this kind of incoherence when a group treats strategy-making as a type of goal setting, where “goals” are interpreted vaguely as aspirations or ambitions to be “better.”

Incorporating desires and aspirations into strategy can be especially problematic, placing unforeseen constraints on the very actions needed for strategic coherence. A large-scale agricultural producer, for example, may cite sustainable farming as a core value, but those farming practices may limit its strategic ambition to feed large populations. When values and aspirations multiply, each can create new limits on action, to the point where no action can feasibly satisfy them. Something will have to give. I call the “strategy” in such situations a “null set.” Some values held dear may have to be forgone, so it is important to be clear about what the strategy has to deliver.

Coherence and challenge

Coherence, on the other hand, emerges from a quest to define the most important challenges facing the company and to develop a strategy to meet them. This requires sharp focus. Experience, judgment, and insight are critical, because there are no automatic methods for generating solutions to difficult problems. Writing about solving hard design problems, industrial design specialist Kees Dorst nicely describes this sense of zeroing in: “Experienced designers can be seen to engage with a novel problem situation by searching for the central paradox, asking themselves what it is that makes the problem so hard to solve. They only start working toward a solution once the nature of the core paradox has been established to their satisfaction.”

The crux of strategy. A strategy is a mixture of policy and action designed to surmount a high-stakes challenge. I underscore “high stakes,” because if the challenge isn’t really important, it’s not strategic. The crux of a challenge is what makes it hard—it’s what makes it a challenge—just as the crux of a rock-climbing route, such as an awkward overhang or a stretch of sheer rock face, is the most difficult part of the ascent.

In dealing with strategic challenges, it is crucial to use the crux principles. First, accept a challenge only if there is a good chance of solving its crux. If the crux is so difficult that it resists solution, then that challenge should be set aside for another day. Don’t choose to fight losing battles if there are others you can win. Second, the crux of the most important, yet solvable, challenge is also the true crux of your strategic situation. Third, we gain coherence by restricting strategic actions to this true crux—or at least by not taking on more than one or a very few critical challenges beyond it. This type of focus automatically increases the chances of success and reduces the inefficiencies that arise from constantly trading off between competing interests and actions.

A focus on challenges, rather than on goals and ambitions, is extremely useful for leaders seeking to stimulate thoughtful dialogue about the choices they face, and it helps avert the kind of haphazard decision-making that gives rise to strategic incoherence. By diagnosing the origin and structure of challenges and considering the actions required to resolve them, we come face-to-face with the need to make actions coherent and lay bare inconsistencies among proposed action-solutions. When starting strategy work, avoid the language of goals and ambitions and, instead, emphasize the logic of challenges, policy, and action. I start my own search for the crux of a challenge simply by asking, “What makes this situation so hard?”

In early 2020, I led a small group of executives through an exercise aimed at assessing the challenges facing a technology company. (No one in the group was associated with the company we scrutinized, and the documents we read were all from public sources.) The technology provider had been an innovator, always on the leading edge of its industry. But by 2019, the company faced obvious challenges. Maturing technologies meant that innovation and performance enhancement opportunities were fewer and farther between. Forays into new product markets had failed, and the company’s culture seemed to be rooted in past triumphs. Add to this glitches marring productivity, plus fierce competition, and the company was facing a crisis. But what was the crux problem?

In all, the group identified 11 key challenges. To pare down the list, the five participants scored each challenge, from one to ten, on its importance (how critical is it?) and its addressability (was there a good chance it could be surmounted over the next three to four years?). The two highest-scoring challenges—manufacturing problems and company culture—were dubbed “addressable strategic challenges.” The manufacturing challenges, which were judged to be more addressable than company culture, were clearly the crux issue for near-term survival. The culture issue was deemed the crux with respect to developing new growth platforms.

Scoring challenges for their addressability and importance can reveal strategic priorities.

Plotting one company’s crux challenges

- Two most extreme challenges by both measures

-

Tech maturationTechnology maturation slowing down innovation

-

Failed productsFailed products in new markets

-

Manufacturing problemsManufacturing problems

-

Customer shiftsIssues airising from customer shifts to the cloud

-

CompetitorsCompetitors taking aim at legacy products

-

5G product issuesThe history of problems associated with 5G product issues

-

Subsitute productsSubsitute products replacing the company’s core offerings

-

Internet of thingsThe Internet of Things opportunity

-

Ai innovationsNew product and service offerings associated with Ai

-

ChinaThe opportunities and growing associated with production and sales in China

-

CultureA culture in which past triumphs inhibit risk taking

Focus, policy, and action. Keeping a business singularly focused on a specialized competitive differentiator tends to support strategic coherence. A useful example is Petzl, a private French company that makes high-performance climbing, caving, skiing, and industrial-safety equipment. In an article in SGB Media, a consumer-goods industry publication, Mark Rasmussen, then the president of Petzl America, articulated his company’s strategic focus succinctly: “Petzl is not specialized in rock climbing, work at height, or cavers, but creates tools for anyone who is trying to move up or down under the constraints of gravity.”

The challenges for a company making climbing equipment are quality and trust. If your life depends on a small piece of equipment, you have to trust the quality of that product and its maker. There are hundreds of firms making outdoor gear, but which of them would you trust to make a self-braking belay device that won’t snap in extreme cold or have some other hidden flaw: a company that’s focused exclusively on climbing equipment or one that also sells fashionable outerwear and casual boots? When it comes to climbing gear, only a few firms pass this test of quality and trust. Petzl is possibly the leader, followed by Black Diamond Equipment, which, like Petzl, is led by a real-life climber.

Many of the strategy cases taught in management programs examine highly coherent firms in which each policy and action contributes to the overall competitive punch. In this vein, Southwest Airlines’ original low-cost strategy, Ryanair’s bare-bones approach (which was modeled on Southwest’s), and Netflix’s original DVD-by-mail business are all examples of companies adopting tightly knit coherent strategies.

Large, complex organizations have a harder time achieving singular focus, due to the diversity of their business and, sometimes, to the abundance of resources at their disposal. When resources seem plentiful, it is tempting to try to deal with a host of issues at once. This, unfortunately, tends to produce policies and departments working at cross-purposes with one another. Strategic Coherence, on the other hand, is advanced by crafting policies and actions that do not fight against one another. If your future is based on an important R&D project, don’t cut R&D to hit your quarterly earnings target. If your product is distributed through dealers, be careful about also trying to sell directly over the internet. If you are the CEO of an integrated IT hardware and software provider, with a lock into traditional IT departments in the world’s major companies, don’t try to make your cloud services compatible with a separate, open-source cloud infrastructure project—you will weaken both offerings. If your company has a worldwide reputation for fine quality, don’t weaken that by cutting corners in order to meet yesterday’s growth targets in a recession. Preserve your reputation and grow later.

Think again

Why doesn’t everyone approach strategy in this way? Beyond the issues I’ve already laid out—too much emphasis on mission and vision statements, or on vague aspirations—I’d also flag a few other reasons. One is that doing this kind of strategy work is hard. Most strategic challenges are complex and do not lend themselves to predetermined choices or to clear connections between proposed actions and outcomes. It’s easy to walk into traps, like using improper analogies that distort instead of clarify the structure of the challenge.

Human nature also plays a role. Many executives dislike talking about difficulties, which can stall progress. At one strategy retreat, a CEO told me not to mention the fact that the underlying technology supporting his company’s product was becoming stagnant. He said, “I don’t want the team distracted from working on their goals.” Another quoted Peter Drucker, who wrote that organizations should be “directed toward opportunity rather than toward problems.” That’s true. But it’s also true that pretending strategic challenges don’t exist is bad leadership.

Finally, politics and power dynamics tend to distort analysis, by bending it toward what the leader wants to hear, or toward what the analyst thinks the leader wants to hear, or toward the analyst’s own agenda. When I interviewed Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in 2005, he told me, “As SecDef, I have access to just about any expertise imaginable…. The real problem is [that]…each morsel of expertise comes with an agenda attached. It comes from a person or group with a perspective, an ax to grind, a budget to manage, a contract to renew, a career to push forward, and so on.”

These issues are omnipresent for organization leaders. While there’s no silver bullet for addressing them, I’d suggest that a focus on strategic challenges can help, as can a fresh mindset, particularly in times like ours when our core business assumptions are being called into question. Adam Grant captured that mindset well in the title of his book Think Again. “Think again” is a powerful cure for errors in reflexive thinking. Consider this classic question: “If it takes two machines two minutes to make two gizmos, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 gizmos?” The answer many people give, even MIT students, is 100 minutes. You may have to “think again” to get it right: 100 machines will make 100 gizmos in two minutes.

Thinking again allows you to come at a question or challenge in a different way and work out the implications of your first-impulse answer. Most executives, most of the time, have an intuitive sense of what to do about a problem or issue. Along with experience and a sound intellect, these intuitions are the essence of expertise. But in unfamiliar strategic situations, the cost of running with your intuition can be very high. That’s exactly where today’s leaders find themselves—at an inflection point, with their strategic direction called into question. Leaders who step back and think again are taking an important step toward identifying the true crux of their challenge and developing a coherent strategic response.