Projecting what the future holds is an important exercise for business and governments looking to plan ahead. In our first edition of 2021, we look ahead to the trends we expect to come to the fore in the global economy in the year to come.

We identify three themes this year:

Global economy projected to grow at record speed

In our main scenario we expect the global economy to expand by around 5% in market exchange rates, which is the fastest rate recorded in the 21st century. Our projection is conditional on a successful deployment and spread of effective COVID-19 vaccines and continued accommodative fiscal, financial and monetary conditions. Nevertheless, the next three to six months will continue to be challenging, particularly for the Northern Hemisphere countries going through the winter months as they could be forced to further localised or full economy-wide lockdowns (as recently displayed in the UK). Output in some advanced economies, for example, could contract in Q1 of the year. We think that economic growth is more likely to pick up in the second half of the year, which is also when we expect large advanced economies to have vaccinated a substantial share of their population.

...but the recovery will be uneven across sectors, countries and income levels

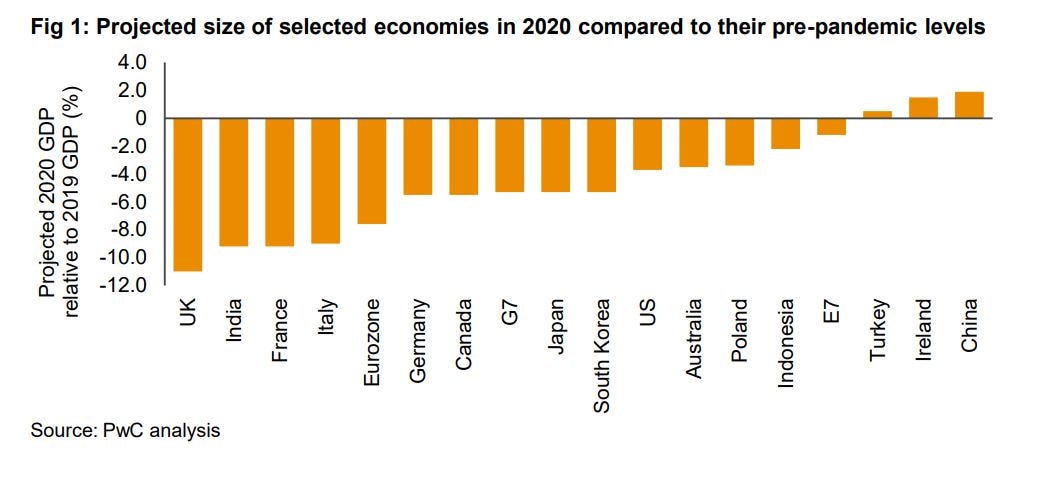

By the end of 2021 or early 2022, we expect the global economy to revert to its pre-pandemic level of output. However, this picture masks an uneven pattern. At one end of the spectrum is the Chinese economy, which is already bigger compared to its pre-pandemic size. On the other end are mostly advanced economies which are either service-based (UK, France, Spain) or more focused on exporting capital goods (Germany, Japan) and are unlikely to recover to their pre-crisis levels by the end of the year. In these economies, growing but lower levels of output is projected to lead to push up unemployment rates. In its December 2020 economic outlook, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) projects an unemployment rate of around 7% in its member states compared to pre-pandemic levels of around 5.5%. Most of the jobs affected are likely to be those at the bottom end of the earnings distribution which is likely to exacerbate income inequalities. We therefore expect governments’ focus to gradually shift from fighting the COVID-19 virus to dealing with higher unemployment rates by upskilling their workforce and creating jobs in newly emerging labour-intensive sectors.

Synchronised push for green infrastructure

2021 will be the first year where the three main economies or trading blocs of the world — the US, the European Union (EU) and China — will refocus their efforts to fighting climate change. The US is expected to re-join the Paris Accord and host an international climate summit early in the year. EU member states are expected to finalise their plans to accelerate the transition towards a greener (and more digital) economy by the end of April. The EU Commission is then expected to release the first tranche of grants and loans worth around 0.5% of Eurozone GDP (or 5% over five years) to speed up the process. Finally, China’s 14th Five Year Plan is expected to be put to action — part of which includes increasing energy efficiency. This and other issues are also expected to be discussed at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow later this year.

Predictions 2021

Italy expected to re-join the $2 trillion club...

According to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) latest estimates, Italian GDP is expected to top the $2 trillion level, re-joining seven other economies including the US, China, Germany and India. The latter was also the fifth largest economy in market exchange rates in 2019, having overtaken both the UK and France. But changes in exchange rates along with the impact of the pandemic means that India is likely to be the seventh largest economy in the world in market exchange rates in 2021, overtaken this time by the UK and France. This is likely to be temporary as, based on current trends, India is again poised to overtake France and Germany before the middle of this decade.

Fig 2: GDP of the largest economies in the world in nominal USD terms

|

2019a |

2020p |

2021p |

US |

21.4 |

20.8 |

21.9 |

China |

14.4 |

14.9 |

16.5 |

Japan |

5.1 |

4.9 |

5.1 |

Germany |

3.9 |

3.8 |

4.3 |

India |

2.9 |

2.6 |

2.8 |

UK |

2.8 |

2.6 |

2.9 |

France |

2.7 |

2.6 |

2.9 |

Italy |

2.0 |

1.8 |

2.1 |

Brazil |

1.8 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

a:actual p: projection

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook

Public debt levels in G7 projected to exceed $57 trillion...

Estimates from the IMF’s October 2020 World Economic Outlook show that the G7 public debt is projected to increase by around $4 trillion in 2021, which is significantly lower than the $7 trillion increase recorded last year. In relative terms, this translates to a public debt level of around 140% of G7 GDP, reflecting the level of support workers and businesses continue to require as we gradually exit the health emergency. By comparison, in the Emerging 7 (E7) economies, public debt is expected to increase by around $2 trillion.

Is this something to worry about? The key rule for public debt sustainability is for real GDP to grow at a faster rate than the level of real interest rates incurred on public debt. Given the level of extraordinary monetary support available combined with the Great Rebound in economic activity rates implies this condition will be met.

Lower for even longer?

In August 2020, the US Federal Reserve completed a review of its mandate and decided to move to an average inflation targeting regime, which is more focused on employment levels (rather than the natural rate of unemployment, which is a theoretical concept). In practice, this means that the Federal Reserve’s target rate is likely to remain lower for longer than previously anticipated (see Figure 3).

The European Central Bank (ECB) is also undergoing a strategic review of its monetary policy strategy. The results are likely to be announced in the fourth quarter of 2021 and there are some signals that the ECB could follow a similar path set by US policymakers last year. Accommodative monetary policy is therefore expected to continue in 2021.

Global green bond issuance expected to top $500billion for the first time

Regional efforts to curb carbon emissions (EU Green New Deal) as well as international agreements (e.g. Paris Accord) require vast sums of investment in green infrastructure in the coming decades

Green bonds, which are used to directly finance environmental projects, currently make up less than 5% of the global fixed income market. In 2021 we expect total green bond issuance will top half a trillion US dollars for the first time (see Figure 4).

This trend is further likely to be helped by the EU Green Bond Standard, which is expected to bring a level of standardisation to these financial instruments.

Finally, we expect investor appetite for Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) funds to continue to increase. Specifically, in an optimistic scenario we think that up to 57% of total European mutual fund assets could be held in funds that consider ESG by 2025. (See our research on this topic here).

Oil price to remain below $60bbl but likely to pick up in second half of year...

Even though oil prices have lately recovered from the lows in 2020, we think that they will continue to remain relatively subdued. Barring any shocks or geopolitical developments in the Middle East, demand for oil, particularly from the Northern Hemisphere economies, is likely to remain subdued for the first six months of the year (even though it has recently picked up in China). It is more likely to increase in the second half of 2021 as the COVID-19 vaccine becomes more widespread and economic activity accelerates. A similar pattern is expected for oil production levels, with supply expected to remain far below pre-crisis levels in the first half of the year before gradually increasing as demand returns.

…but electricity production from renewables is projected to continue to gather momentum:

Despite fossil fuels being the dominant source of electricity generation we continue to expect that solar PV (Solar Photovoltaics) capacity will grow at rapid rates on the back of growing capacity in the EU, India and China. If current trends continue, solar PV capacity is on course to surpass natural gas in 2023 and coal in 2024 in the global electricity sector.

Further predictions for 2021

- European Football Championships: With Euro 2020 now set to take place in 2021, we have had one more year to think about our predictions for the tournament. Having watched the Netherlands (our pick in last year’s predictions article) suffer indifferent form this year, we’ve gone back to the drawing board. Instead, we think that France will follow up its success in the 2018 World Cup to take the Henri Delaunay Trophy home. Allez Les Bleus!

- Tokyo Olympics: Our previous analysis of the factors that can explain the number of medals won by each country found that population, average income levels and whether the country is the host nation are all statistically significant factors. Despite the potential for reduced crowds, we predict that the host nation effect will come through again and see Japan beat its record medal haul of 41 registered at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics.

- Elections: National elections are scheduled in countries covering one-third of the European Union’s population. Citizens in the Netherlands, Czech Republic and Germany will head to the polls with the management of the pandemic likely to be front and centre. A potential re-election of the Dutch Prime Minister could end up making him the second longest serving leader in Europe behind the Prime Minister of Hungary, Viktor Orban.