Global growth slows significantly with major economies expected to narrowly avoid officially entering recession, as interest rates continue to climb…

Overall, the global economy is set to grow by 1.6% in 2023, driven largely by China’s re-opening following a prolonged period of lockdowns and strong expected growth in India and other emerging economies.

Following a strong performance in 2022, The US economy is expected to narrowly avoid a recession in 2023, with the firm projecting GDP growth of 0.2% for the world’s largest economy. Meanwhile, mild contractions in economic activity are expected in the UK and some major EU economies such as Germany and Italy.

... As a result, inflation should largely begin to decline, driven by goods prices, however service price inflation may still remain high due to wage pressures

Following several rate hikes during 2022 by the world’s largest central banks and the subsequent slowdown in global demand, goods price inflation is expected to start to ease in 2023, helping drive down overall inflation rate projections in several economies across the world, as can be seen in the chart below.

On the other hand, service price inflation may take longer to come down. Now that inflation has fed into workers expectations and the global labour market generally remains tight, the upward pressure on wages will likely prop-up service price inflation.

Rising interest rates means that expansionary fiscal policy, used by Governments after the pandemic, will become more expensive going forward…

In our last publication, we argued that after inflation, the next big topic in economics is going to be around government debt, for three reasons: the amount of debt is increasing, GDP growth is slowing, and the cost to service that debt is also increasing, due to the recent increase in interest rates by major central banks.

We maintain this view, although note an amelioration in economic outlook since then, with projections regarding economic activity being slightly more upbeat than they were in mid-2022.

Nonetheless, government bond yields continued to rise over the second half of 2022, making debt servicing more expensive.

The ‘humped’ shape of global yield curves implies markets expect interest rates may continue to rise somewhat, before coming down again…

Typically, liquidity preference theory implies that yield curves are upward sloping, i.e. investors are compensated with higher interest rates for investing in longer-term securities (this is the case with Malta’s yield curve as at today, as shown in chart).

However, at the moment, US and EURIBOR yield curves are upward sloping up to around one-year maturity, before turning largely downward sloping from 2 year maturity onwards. This ‘kink’ in the yield curve implies that liquidity preference theory is being offset by investors’ expectations of a short-term increase in interest rates, to be followed by medium-to-long term period of declining rates.

This could be interpreted as markets having a bearish outlook for the medium to long term, anticipating that after a few more rate hikes during the year, central banks will then cut back on interest rate increases once inflation begins to recede and the economy slows down.

In fact, downward sloping yield curves are often associated with pessimistic economic outlooks, as investors increase their demand for long-term maturities (which offer more safety as they lock-in a rate for a longer period), which pushes up the prices of long-dated bonds, thus lowering their yields.

On the other hand, some analysts argue that the fact that the shape is ‘humped’ rather than entirely downward sloping may not imply such a pessimistic outlook, but merely more of an indication of currently unsettled markets which are pricing-in offsetting potential monetary policy responses to an ambiguous economic outlook.

Amidst this uncertainty, Malta’s yield curve has remained upward sloping, possibly because of the dominance of the Central Bank of Malta as a market maker in the local bond market.

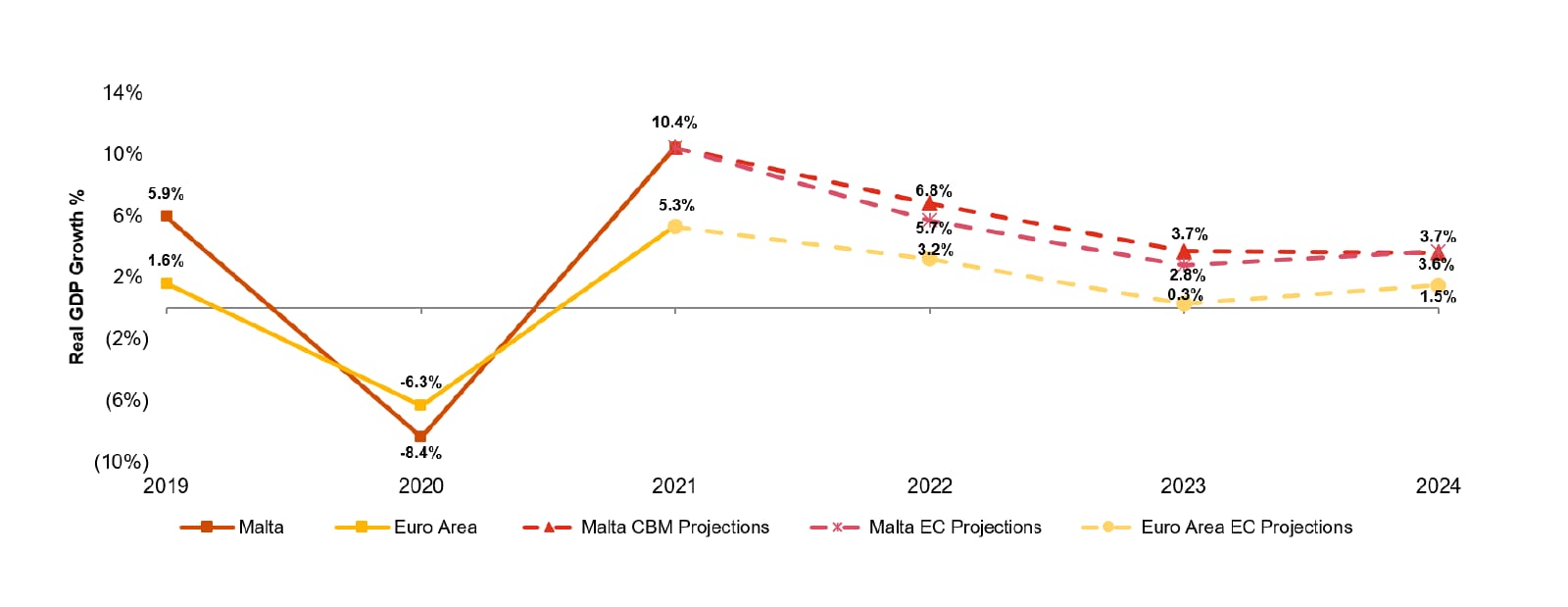

Amidst a challenging international economic environment, Malta’s economy has surprised on the upside in 2022, with expectations of relatively robust growth to continue in 2023 and 2024

While Malta’s small, open economy is definitely not immune to international developments, economic data for 2022 point to a relatively strong performance, with the Central Bank of Malta expecting growth for FY22 to stand at 6.8%, normalising to 3.7% and 3.6% in 2023 and 2024 respectively.

Consistent with previous assessments, the drivers of such growth in 2022 were private consumption and exports (tourism). Tourism’s contribution to growth is expected to diminish for 2023-2024, following the stronger than expected rebound in 2022.

Source: European Commission, Central Bank of Malta

While relatively low from an EU perspective, inflation in Malta has picked up in the second half of 2022, but is expected to moderate in 2023

The main reason why Malta’s headline inflation rate has remained the lowest in the eurozone so far, is that fuel and electricity prices remain fixed as a result of state intervention. The big question is how long can the State sustain such low prices.

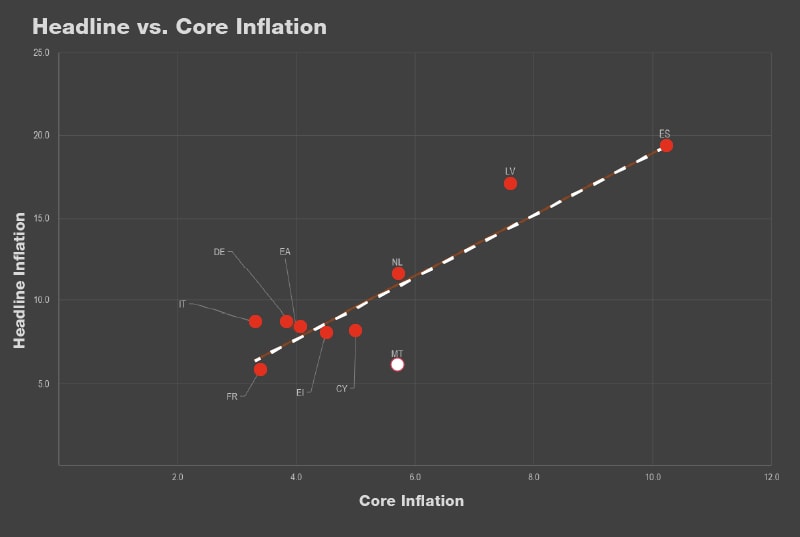

A closer analysis of Malta’s inflation shows that while headline inflation is below EA average, core inflation is above average

Source: Eurostat

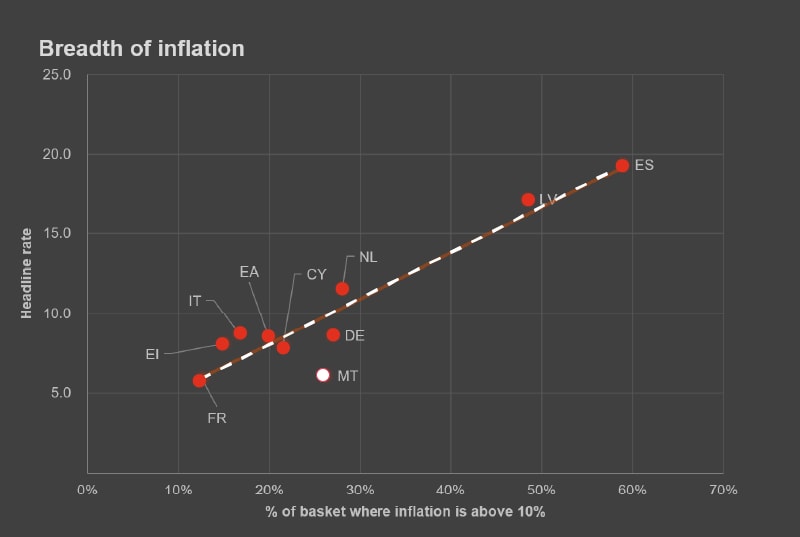

Furthermore, the breadth of inflation in Malta appears wider than the euro area average, implying that price growth appears to be more broad-based across different components in the local economy than the euro area on average

Source: Eurostat

While the ECB has increased interest rates on the main refinancing operations (MRO) five times in the past seven months, from 0.50% to 3.00%, Maltese commercial banks have largely not yet passed this through to local mortgage rates, as their exposure to ECB loans is relatively low

From a local perspective, while yields have risen sharply over the past months, the passthrough of ECB interest rate hikes to local lending has not yet materialised. One reason for this could be that Maltese banks’ exposure to ECB loans is relatively low, instead largely funded by a strong local depositor base.

On the other hand, the significant increase in MGS yields (observed at around 4% for long-term bonds) implies that existing home loans at current mortgage rates are relatively less profitable for banks, given that more liquid and risk-free borrowing from Government bonds is available at a relatively higher return. Then again, while bond yields do not carry credit risk, they are susceptible to market movements going forward, while mortgages are less so. The increased opportunity cost arising as a result of higher MGS yields will no doubt weigh on banks' future decisions regarding interest rates on lending.

A recent study published by the Central Bank of Malta indicates that the local market can sustain an increase of up to 150 basis points in mortgage interest rates, while an increase of 250 basis points would imply significant strain on financial stability

As per the latest financial stability report published by the Central Bank of Malta (which evaluates the resilience of the financial system in Malta and identifies sources of potential systematic risk), an interest rate shock of 150 basis points would not result in significant build up of risk as, in their assessment, borrower-based metrics would remain relatively sustainable.

However, interest rate increases of up to 250 basis points would make it more difficult for a significant portion of households to repay their loans, as over 25% would have a loan service-to-income ratio that is higher than 40%. This would mainly impact those borrowers who at the origination of the loan had already stretched borrower metrics. Around half of such borrowers represent first-time buyers with a loan-to-value of more than 80%, a loan-to-income of more than six times and a term to maturity of more than 30 years.

In summary, while Malta’s economic activity has surprised on the upside and is expected to outperform EU average, it remains important to continually monitor price growth dynamics, especially within the context of increasing international interest rates

The year 2022 has seen the largest increase in the cost of living in a generation, with central banks responding with a sharp, quick succession of interest rate hikes, resulting in an increase in the cost of borrowing for governments, companies and homeowners alike. Private and public indebtedness is significantly more expensive than it was a year ago.

Amidst this backdrop, Malta’s economy continues to outperform euro area average in terms of growth, driven largely by domestic demand and net exports, in turn reflecting a strong bounce-back in tourism. Meanwhile, while headline inflation is relatively low, core inflation in Malta is picking up and appears relatively high when compared to European peers. Also, the breadth of inflation in Malta is above the euro area average implying that it is relatively widely broad-based across components and not concentrated in a few high-inflation components.

Clearly, inflation is not dead yet, with underlying price pressures still mounting and an international yield curve which implies that core inflation may not have peaked just yet. The extent to which rising international interest rates feed into the local economy and the potential implications on local economic performance remain to be seen.

Contact us