Authors

As global demand for electric vehicles (EVs) experiences slower growth, many automotive companies are recalibrating their strategies. There is a noticeable shift from EV commitments towards a renewed focus on internal combustion engine (ICE) development combined with hybrid systems as consumers grapple with changes in behaviours required with EV ownership compared to traditional fossil fuel vehicles.

In response, automakers are turning their attention to hydrogen as an alternative pathway to wean us off our reliance on fossil fuel vehicles. Several automotive giants have been touted as pioneers in the hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEV) technology and traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles which burn hydrogen, and are also developing hydrogen-powered ICE, which are seen as particularly useful for heavy equipment in remote locations.

According to the Energy Commission of Malaysia, our country reached a peak of 13,000 kToE (kilotonnes of oil equivalent) of motor vehicle fuel usage in 2019 — roughly 18 L³ (billion cubic litres), enough to fill about 7,400 Olympic-sized swimming pools. A replacement of any material percentage of this with an alternative energy source would potentially prove to be lucrative for any party willing to embark on such projects. First, it's helpful to understand hydrogen composition and the technologies used.

Hydrogen: More to it than meets the eye

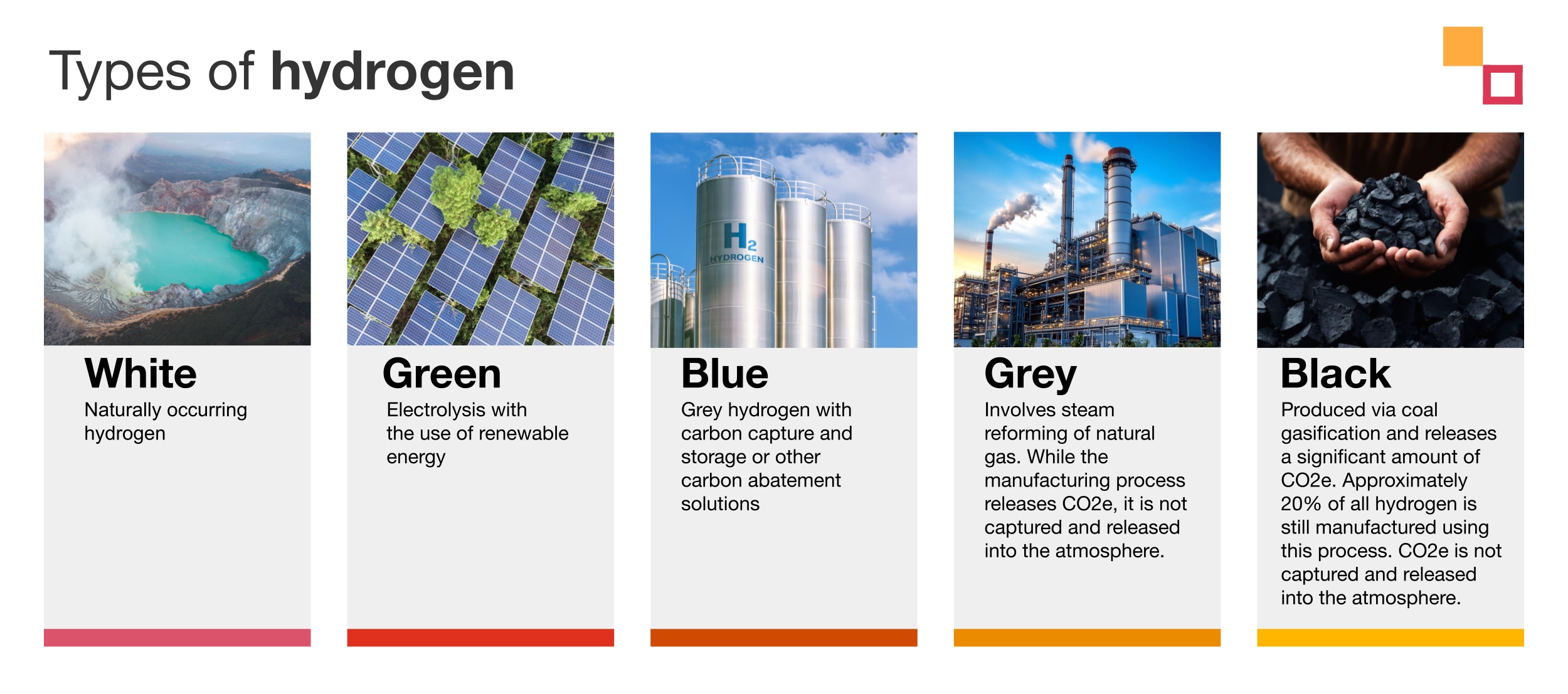

Hydrogen is a colourless gas which can be broadly classified into multiple categories according to the colour spectrum depending on their feedstock and manufacturing process. The most common types of hydrogen can be seen in the following illustration:

It is worth noting that there are no universally recognised standards for hydrogen classification but these are generally accepted terminology within the industry.

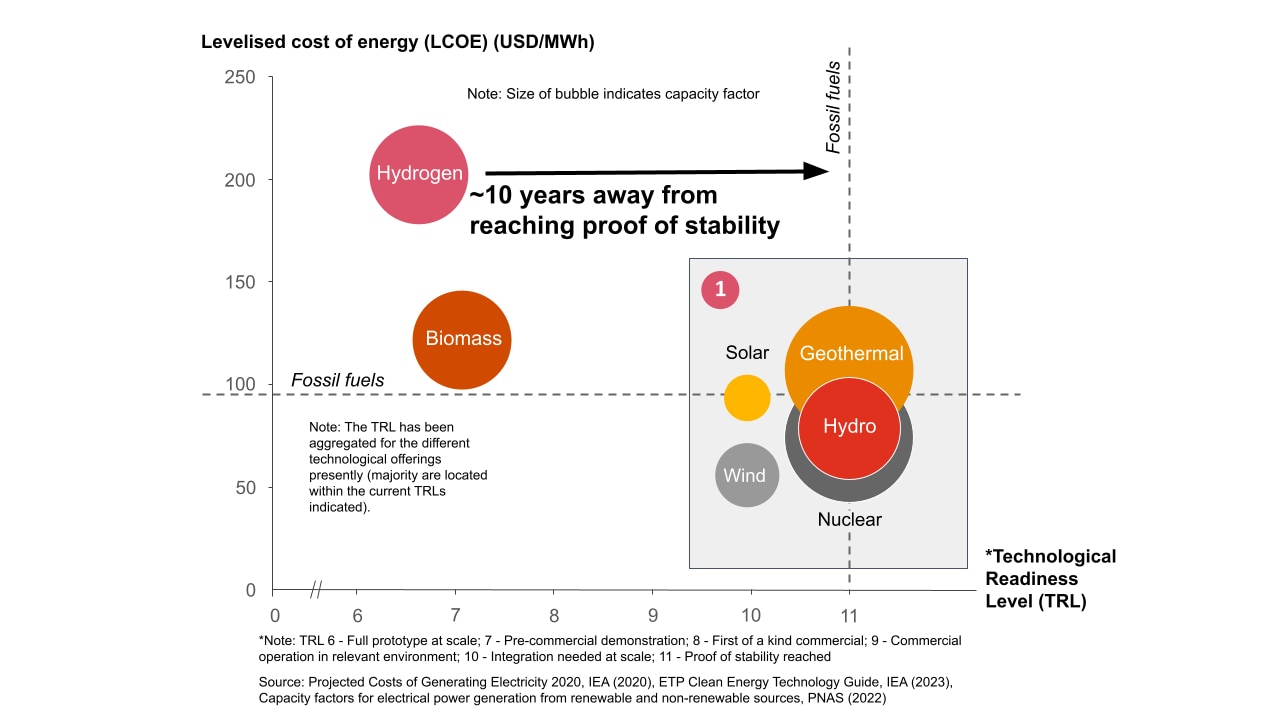

Hydrogen-based fuels utilise green hydrogen combined with CO2 to produce carbon-neutral synthetic fuel that is compatible with modern ICE vehicles. Green hydrogen is currently expensive, but it is expected to reach a cost parity with other clean energy sources within the next decade (refer to diagram). Linking carbon capture and storage (CCS) to hydrogen production could be an interim solution worth exploring.

CCS in hydrogen - A match made in heaven?

As it stands, the production process for the vast majority of available hydrogen - specifically black and grey hydrogen - releases significant CO2 and requires substantial energy. However, a low-emission hydrogen employing CCS technology can be crucial in the interim, as the cost parity of green hydrogen to cheaper sources of hydrogen reduces. This would be a crucial pathway to reduce the existing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions globally while addressing issues around availability of other commercially viable renewable and cleaner energy sources at present.

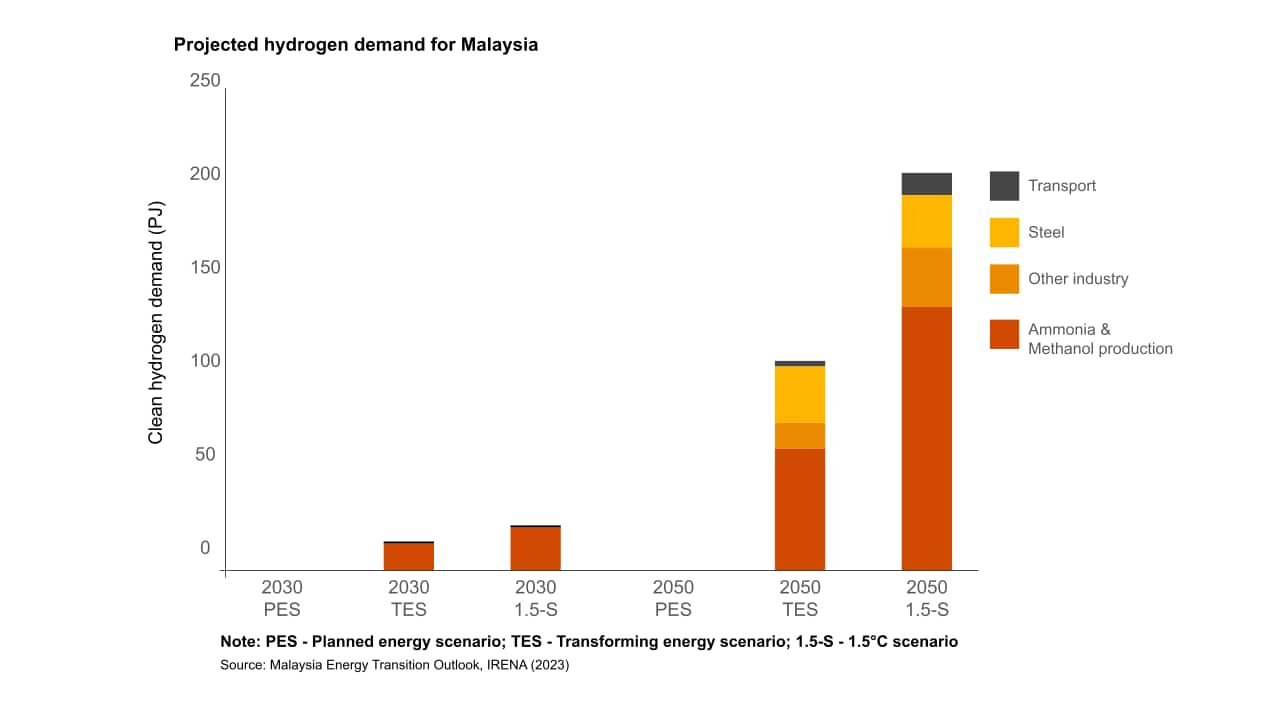

We also need to be cognisant that there are sectors where hydrogen is one of the few alternative energy sources to decarbonise. Time is of the essence - with a global decarbonisation rate of only 1.02% in 2023 (the lowest in over a decade), the world needs to press the pedal on decarbonisation, i.e. 20 times faster to limit warming to 1.5°C, above pre-industrial levels, according to PwC's Net Zero Economy Index 2024.

Blue hydrogen, manufactured through steam reforming with subsequent CO2 emissions captured in flue stacks for storage represents a viable transitionary pathway. It can be deployed to bridge the gap between grey hydrogen, which emits high levels of CO2, and green hydrogen, which is cleaner but currently more costly to produce. Depending on the region, green hydrogen can cost up to 4 times more than grey hydrogen.

Policy interventions across the ecosystem

The country's growing interest in developing its CCS industry with announcements of planned CCS hubs in the states of Terengganu and Pahang bode well for the development of low-emission hydrogen. Coupled with the existing oil and gas sector, Malaysia is well positioned to be a significant player in the low-emission hydrogen market as it develops green hydrogen offerings in Sarawak. The development of such a sector would spur advances in other peripheral activities that serve the sector such as carbon storage as a service (CSaaS), infrastructure development for hydrogen transportation, operations and maintenance service. These services would ultimately create new job opportunities across the value chain.

As with any nascent technology, support is required from both the supply-side and demand-side of the spectrum to address risks and challenges within the ecosystem. Hydrogen infrastructure such as transportation and refuelling for private consumption would require significant investment to ensure adequate network coverage and supply capacity. We would need to build this infrastructure, bearing in mind that the petrol station, as we know it today, took 100 years to evolve from the time since the first widely available motor vehicle, the Ford Model T, was introduced.

Consumers would need to be convinced about switching, especially without any added cost benefits over their ICE counterparts or other forms of personal modes of transport. This issue is further exacerbated by the affordability of ICE-alternative vehicles such as FCEVs, Battery Electric Vehicle (BEVs) and Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEVs). The affordability gap is stark — 40% of total new car sales in Malaysia in 2023 fell within the RM45,000 to RM55,000 median price range whereas the median EV price stands at RM250,000.

Summary

Malaysia’s hydrogen industry needs to move fast if the country aspires to become a leading producer in the region. The shift in energy transition from fossil fuels to hydrogen is an opportunity to revamp the energy sector. To achieve this, it requires support on both supply and demand side to spur deployment of hydrogen. Being able to access readily available technology and established logistical infrastructure that can support hydrogen would facilitate this growth. Incentives and grants to promote the commercial viability of hydrogen and CCS projects as an encouraging source of economic growth could be welcomed in the Budget 2025. Whilst change will not happen overnight, developing Malaysia's hydrogen economy potential should be a focus for energy transition and should be expedited.

Contact us