Tax Insights: Updated legislation ─ Excessive interest and financing expenses limitation (EIFEL) regime

November 16, 2022

Issue 2022-29

In brief

On November 3, 2022, the federal government released the 2022 Fall Economic Statement, as well as updated draft legislation for the proposed excessive interest and financing expenses limitation (EIFEL) rules.

Most notably, the revised draft legislation defers the effective date of the rules, to taxation years beginning after September 30, 2023. The Department of Finance has also opened a second consultation period on the rules, which closes on January 6, 2023, giving taxpayers additional time to consider and provide feedback on the revised draft legislation.

The deferral of the effective date for the EIFEL rules is welcome. It should provide certain taxpayers with more time to plan for the impact of these rules on their financing arrangements. However, the revised draft legislation includes significant areas of additional complexity, which certain taxpayers must consider to ensure they understand how these rules affect their business. Notably, the EIFEL rules are now explicit in applying to controlled foreign affiliates, which could add significant complexity to any modelling calculations undertaken to date.

This Tax Insights discusses the changes to the proposed EIFEL rules and the potential impact of these changes for taxpayers.

In detail

The EIFEL rules restrict the deduction for interest and financing expenses (IFE) of certain taxpayers to a proportion of their earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) computed for tax purposes (adjusted taxable income). For more background information, including the detailed operation of these rules when draft legislation was first released on February 4, 2022, see our Tax Insights “Excessive interest and financing expenses limitation (EIFEL) regime.” Subsequently, on November 3, 2022, the Department of Finance released significant revisions to the draft EIFEL legislation, based on comments received during the initial consultation period last spring.

New effective date and reduced transitional period

The fixed ratio is the primary operational rule of the EIFEL regime; it restricts the deductibility of interest and financing expenses based on a fixed percentage of adjusted taxable income (ATI) (subject to other available relief from the rules). Under the original EIFEL proposals, the fixed ratio was to be 40% for taxation years beginning in 2023, and 30% thereafter. In the revised draft legislation, the fixed ratio is:

- 40% for taxation years beginning after September 30, 2023 and before January 1, 2024

- 30% for all taxation years beginning after December 31, 2023

Taxpayers with calendar taxation year ends will therefore become subject to the EIFEL rules in 2024, with the 30% fixed ratio applying immediately (without any transitional year with a 40% ratio).

There are anti-avoidance rules that could apply if any transaction, event or series is undertaken with a purpose of deferring the application of the EIFEL rules, or extending the period that the transitional 40% fixed ratio would otherwise apply.

PwC observes

The deferral of the coming into force date for the EIFEL rules is a welcome change, which will give many taxpayers more time to understand the impact of the rules on their financing arrangements. The “cost” of this deferral is the elimination of the 40% fixed ratio transitional rule for impacted taxpayers – subjecting these taxpayers to the more restrictive 30% fixed ratio when the EIFEL rules take effect. The 40% fixed ratio will apply only to taxpayers with taxation years beginning between October 1 and December 31, 2023. The anti-avoidance rules may need to be considered if a transaction creates a deemed year end in this period, or changes the normal taxation period of a taxpayer.

Scope of the rules

As a starting point, the EIFEL rules apply to all corporations and trusts, as well as to partnerships on a look-through basis by including relevant amounts in the EIFEL calculation of a corporate or trust partner. However, if an entity is an “excluded entity” it can be exempt from these rules. In addition, a new carve-out for “exempt interest and financing expenses,” relating to certain Canadian public-private infrastructure projects, has been introduced.

Excluded entities

The revised legislation includes updates on all three of the definitions of an “excluded entity.” Two exclusions based on de minimis thresholds are updated as follows:

- Canadian-controlled private corporations (CCPCs) with taxable capital employed in Canada of less than $50 million are now excluded from the EIFEL rules – this threshold has been increased from the originally proposed $15 million, to align with the 2022 federal budget measure that raises the top end of the phase-out range for the small business deduction.1

- The Canadian group net interest expense threshold is increased to $1 million (from the previously proposed $250,000).

The third “excluded entity” test excludes certain businesses that operate almost entirely in Canada, provided certain conditions are met. The November 2022 draft legislation extensively updates this definition as follows (noting that all of these conditions must be met to fall within the third definition of excluded entity):

- The Canadian taxpayer and all other group members carry on all or substantially all of “the businesses, undertakings and activities” in Canada (this is extended from the all or substantially all of “each business” requirement in the February proposals).

- A new permitted foreign affiliate holding is added, requiring the value of the group’s foreign affiliate holdings to be less than a $5 million de minimis threshold; for this purpose, the value of the group’s foreign affiliate holdings is calculated as the greater of: (i) the Canadian Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) balance sheet value of the stock of all of the foreign affiliates, or (ii) the fair market value (FMV) of all property of the foreign affiliates.

- The requirement that no non-resident person be a specified shareholder or a specified beneficiary (as defined in subsection 18(5) of the Income Tax Act [ITA]) is expanded to also prohibit a partnership from owning more than 25% of the equity in the particular taxpayer (or any eligible group entity) if more than 50% of the FMV of the interests in the partnership are held by non-residents.

- The limitation on situations where all or substantially all of the IFE of the taxpayer (or an eligible group entity) is payable to a tax-indifferent investor, is relaxed to apply only to tax-indifferent investors that do not deal at arm’s length with the taxpayer (or any eligible group entity in respect of the taxpayer). There is also a revision to the anti-avoidance rule for excluded entities (in new ITA subsection 18.2(14)), which deems certain persons to be a tax-indifferent investor. The revisions include making the anti-avoidance rule a main purpose test and limiting tax-indifferent investors to only those with which the taxpayer (or an eligible group entity) does not deal at arm’s length.

Sector-specific exclusion – certain public authority projects

A significant change to the IFE definition is a new carve-out for “exempt interest and financing expenses” (exempt IFE). This exemption removes from IFE amounts incurred by a taxpayer (or a partnership of which the taxpayer is a partner) in respect of borrowings made in the context of certain Canadian public-private partnership (P3) infrastructure projects, effectively exempting such borrowings from the EIFEL rules.

For an amount of IFE to qualify for this exemption, the following conditions must be met:

- the borrower must have entered into an agreement with a public sector authority to:

- design, build and finance, or

- design, build, finance, maintain and operate,

real or immovable property owned by a public sector authority

- the borrowing must have been entered into by the borrower in respect of the above agreement

- it must reasonably be considered that all or substantially all of the IFE incurred is directly or indirectly borne by the public sector authority, and

- the IFE amount must have been paid or payable to persons that deal at arm’s length with the borrower (other than any person or partnership that is, or does not deal at arm’s length with, a person or partnership that has a direct or indirect equity interest in the borrower)

Exempt IFE is excluded from the computation of IFE, and is not added back when computing ATI. Income earned by a borrower in respect of a borrowing that generates exempt IFE is also excluded from ATI. This means that borrowings exempted under this rule, and income from the projects funded by such borrowings, are effectively excluded from the EIFEL calculations.

PwC observes

While the de minimis exemption for groups with less than $1 million net interest expense represents a significant increase from the earlier proposals, it is still far below the thresholds adopted by other jurisdictions that are following the recommendations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD’s) BEPS Action 4 report (for example, the United Kingdom has adopted a £2 million threshold, which, at the time of writing, is equivalent to around $3 million). Having a lower threshold could make Canada a less competitive jurisdiction for debt financing than other countries that have adopted similar OECD interest deductibility measures.

Within the third excluded entity test, the broadening of the all or substantially all business test should enable entities with multiple businesses to apply the all or substantially all test on an aggregated basis for multiple businesses. As previously drafted, the test was required to be applied to “each business,” meaning a single business with a substantial foreign component could breach the condition even when the business was small relative to the size of other businesses of the taxpayer or eligible group entity.

The foreign affiliate de minimis threshold provides for a more generous position than the initial draft rules, which precluded any corporation or trust, or eligible group entity, with any foreign affiliate from meeting this excluded entity definition. The introduction of the $5 million de minimis threshold for foreign affiliates means that Canadian groups with de minimis investments in foreign affiliates should still be able to fall within this excluded entity definition, provided the other conditions are met.

The expansion of the specified shareholder and specified beneficiary conditions appear to be an anti-avoidance provision with respect to entities which might be able to structure investments by non-residents through a partnership. This condition requires that 50% of the FMV of the partnership interest be owned by non-residents. As drafted, this requires all non-resident holdings to be aggregated when testing the 50% threshold, even those of arm’s length persons. In contrast, the specified shareholder and specified beneficiary rules only aggregate non-arm’s length holdings. This also means that an effective interest in the corporation or trust equity of as little as 12.5% could prevent this condition from being met, if structured through a partnership (e.g. a non-resident owns 50% of the FMV of the interests in a partnership, which owns 25% of the FMV of the capital stock of a corporation).

The original restriction on IFE paid or payable to tax-indifferent investors raised concerns regarding entities which have publicly traded debt, more than 10% of which is held by non-residents; there were also concerns around how a group could practically monitor this threshold in a public context. Limiting the restriction on tax‑indifferent investors to only non-arm’s length tax-indifferent investors should alleviate concerns regarding this publicly traded debt.

The public-private partnership infrastructure projects exemption effectively exempts the financing of these Canadian projects from the EIFEL rules. Absent this exclusion, investors in these projects could have faced significant interest restrictions due to the long duration of these highly debt-financed projects. The Department of Finance’s introduction of this exemption is in line with an optional exemption for these public infrastructure projects proposed in the OECD BEPS Action 4 report and is similar to public infrastructure exemptions that other jurisdictions have included in their equivalent rules.

While the exemption addresses EIFEL concerns for public-private partnership infrastructure projects, it is limited to this particular industry; there remain no other sector-specific exclusions in the EIFEL rules. Therefore other highly leveraged sectors must rely on the other relief mechanisms to limit the adverse tax impact of the EIFEL rules – by either transferring capacity from other group entities, or applying the group ratio rules.

Financial institutions

The revised proposals introduce the concept of a "financial institution group entity," replacing the "relevant financial institution" concept used in the original proposals. Financial institution group entities generally include banks, credit unions, insurance corporations, trust companies and entities whose principal business involves lending money to arm's length persons. It also includes certain eligible group entities, in respect of the above financial institutions, that deal in securities and certain entities that perform ancillary activities for these financial institutions. Various changes to the EIFEL rules in respect of financial institutions, which are discussed throughout the remainder of this Tax Insights, rely upon this new definition.

Adjusted taxable income (ATI)

ATI is the defined term for a taxpayer’s “tax-EBITDA” within the EIFEL rules. In the November 2022 draft legislation, numerous changes have been made to the adjustments when calculating ATI, including:

- removal of net capital losses from variable A (which can be either a positive or negative amount), so that the calculation’s starting point is now limited to the taxable income or non-capital loss of the taxpayer for the year

- new addbacks for variable B, for resource pool expense claims and terminal losses, which expand the forms of “tax depreciation” to be added back in determining ATI

- significant changes to the addback in variable B for non-capital losses claimed in the year (while the addback mechanism is complex, the general objective appears to provide an addback only to the extent that the losses derive from net interest and financing expenses [or similar amounts] in the loss year)

- adjustments to variable C (which reduce ATI), including adding:

- recaptured depreciation arising on disposal of a capital asset (including recaptured amounts in a partnership)

- certain amounts in respect of the disposition of resource properties or other recovery of resource expenses

When the taxpayer is a trust, there is a rule in variable B that adds back to the trust’s income amounts that are flowed out to its beneficiaries, which ensures that EIFEL applies at the trust level. This rule is amended so that it will not apply to the extent of dividends received by the trust that are flowed out and designated as taxable dividends, which effectively moves these dividends out of the trust’s EIFEL calculations and into those of the beneficiary. The converse rule in variable C, which applies when the taxpayer is a beneficiary of a trust, is similarly amended. However, that variable C rule is also amended to carve-out certain foreign accrual property income (FAPI) amounts in respect of taxpayers that are beneficiaries of certain non-resident commercial trusts.

Further, additional changes to the definition of ATI have been made to accommodate how the rules now apply to controlled foreign affiliates – this is discussed further in the “Application of the EIFEL rules to controlled foreign affiliates” section below. For variable A, a new loss amount has been introduced, with respect to foreign accrual property losses (FAPLs) of any controlled foreign affiliates. This new negative amount for variable A generally represents the portion of a FAPL that relates to the affiliate’s relevant net IFE, as discussed below. A notable inclusion in variable B of ATI is paragraph (i), which seeks to apply an uplift to ATI to the extent that a controlled foreign affiliate is utilizing a FAPL in the current year which arose in another taxation year. The uplift is provided to the extent of the affiliate’s net interest and financing expenses and generally mirrors the adjustment in paragraph (h) in respect to the utilization of non-capital losses.

PwC observes

The removal of net capital losses in determining ATI resolves the issues around potential double-counting of a reduction to ATI from the creation of a net capital loss. Under the original draft legislation, net capital losses reduced ATI in the year they arose, but there was no uplift adjustment to ATI in the year of utilization, although they would reduce taxable income in that utilization year. Similarly, issues may have arisen if a net capital loss was never utilized, such that a taxpayer could have had a reduction to ATI in the loss year, but never received a benefit from that reduction to ATI. The removal of the net capital loss adjustment therefore appears appropriate given that such losses do not appropriately represent the “tax-EBITDA” of a taxpayer for a particular year, rather representing one-off capital disposal events that could otherwise distort the ATI calculation.

Natural resources and mining groups in particular will welcome the addback for resource pool expenditures, which will increase their capacity to deduct interest in a year in which such amounts are being claimed.

Similarly, the inclusion of other adjustments for capital amounts that are included in taxable income, such as recaptured depreciation and terminal losses, should help provide a more effective view of the “tax-EBITDA” of the entity.

The revisions to the addback for non-capital losses claimed in the year provides a fairer basis for determining how much of the loss being utilized should provide an addback to ATI in the year of utilization, by effectively requiring a calculation of various components in the definition of ATI for the year that loss arose. The original draft rules restricted this adjustment to net interest and financing expenses in the year the loss arose. However, this adjustment will be practically complex, since losses carried forward to reduce taxable income may include years that will have arisen before the EIFEL rules took effect. Taxpayers will need to effectively perform part of the EIFEL calculations for the loss years to determine the ATI impact of applying the loss in the carryforward year.

Interest and financing expenses and revenues

The EIFEL rules deny the deduction of a percentage of a taxpayer’s IFE, which is computed by a formula in ITA subsection 18.2(2). The key elements of this formula are the IFE and interest and financing revenues (IFR) of the taxpayer. The revised draft legislation includes various changes to these definitions.

Interest and financing expenses (IFE)

Variable A of the IFE formula includes various amounts in IFE, including interest and certain other amounts that would otherwise be deductible in computing income. The revised proposals clarify that these tests refer to amounts that would be deductible in the “particular” taxation year – the year in which the EIFEL rules are applied, which may sometimes differ from the year the relevant expenditures were incurred (e.g. capitalized interest that is deducted through the capital cost allowance [CCA] rules).

Paragraph (c), which includes capitalized interest in IFE when deducted as CCA, has been updated to reflect only amounts that are paid or payable on or after February 4, 2022 (the date that the first draft EIFEL rules were released for consultation). IFE also now includes the portion of terminal losses attributable to interest, and certain other financing expenses, paid or payable after February 4, 2022.

As discussed above, IFE now excludes interest and financing expenses which are incurred in respect of certain public-private infrastructure projects.

Certain clarifications have been made to the "cost of funding" rule, which generally relates to arrangements that have the effect of increasing the economic cost of borrowing or other financing. The converse rule, in respect of amounts that have the effect of reducing the cost of funding, has also been clarified. Further, the latter rule has been expanded to include amounts that are derived through a partnership.

A significant change to the definition of IFE is the inclusion of certain amounts of interest and financing expenses of controlled foreign affiliates, as discussed in the “Application of the EIFEL rules to controlled foreign affiliates” section below.

Interest and financing revenues (IFR)

The definition of IFR has been expanded to include deemed interest income in relation to a pertinent loan or indebtedness and accruals in respect of specified debt obligations.

Certain clarifications have been made to the "amounts [...] that increase the return of the taxpayer" rule, which generally relates to arrangements that have the effect of increasing the return of the taxpayer with respect to a loan or other financing. The converse rule, in respect of amounts that have the effect of reducing the return to the taxpayer, has also been clarified. Further, the latter rule has been expanded to include amounts that are derived through a partnership.

Similar to IFE, IFR also includes certain amounts of interest and financing revenues of controlled foreign affiliates, as discussed in the “Application of the EIFEL rules to controlled foreign affiliates” section below.

PwC observes

The specification that the deduction is required in the “particular” year for an amount to be included in IFE is helpful for clarifying that an amount can be paid or payable in any year, but it is the deduction obtained in the “particular” year (i.e. the year in which EIFEL calculations are being performed) that is relevant for determining when to include the amount in IFE.

The restriction of capitalized interest to amounts paid or payable on or after February 4, 2022, is intended to facilitate compliance and should now only require taxpayers to track amounts of capitalized interest that are paid or payable after the first EIFEL proposals were released, rather than requiring taxpayers to look back to amounts of interest that may have been capitalized since an asset was originally acquired. This is a helpful amendment, but does require taxpayers to start tracking amounts now that relate to interest capitalized since February 4, 2022, which may be part of future tax deductions, such as CCA and terminal losses. These grandfathering changes are welcome, but we would note that a similar change may also be helpful in the context of the adjustment to ATI when there is a prior year non-capital loss being utilized in the current year. As currently drafted, this particular adjustment may require the taxpayer to look back to determine various components of the pre-regime loss in a year when the loss arose (including for taxation years before EIFEL applied). Instead, the Department of Finance should consider whether the draft legislation should be further amended to allow a full addback for carried-forward non-capital losses that arose in periods before the release of the EIFEL rules, and then apply the adjusted addback rule for non-capital losses arising in post-EIFEL years only. For further simplicity, we would note that other jurisdictions have not required any adjustment to the addback of the total non-capital losses utilized in determining their equivalent of “tax-EBITDA.”

There remains an issue in the draft rules with respect to capitalized interest amounts, which result in an interest limitation due to the EIFEL rules. Proposed ITA subsection 18.2(3) deems an amount to have been deducted in determining the undepreciated capital cost (UCC) balance (and similar pools for resource property), even though no deduction is permitted for this capitalized interest due to the EIFEL rules. If there is a recapture of depreciation on a disposal of the asset in a later year, and no denied interest amounts have been recovered through the restricted interest and financing expense (RIFE) mechanism, the UCC would be understated such that there would be an overstatement of the recapture. To remedy this, the Department of Finance should consider reducing both the recapture and the RIFE balance.

The clarification on deemed interest income is helpful; however, we note that ITA subsection 17(1) deemed interest income on amounts owing from certain non‑residents does not appear to have been included. It is not clear whether this was a deliberate policy choice from Finance or just an oversight.

Other deemed interest provisions in the ITA are also not explicitly referenced when it would also be fair to the taxpayer to include them in IFR, notably proposed ITA subsection 12.7(3) for an income inclusion under the proposed hybrid mismatch rules2 for financial instruments. As the EIFEL rules are to be applied after applying the proposed hybrid mismatch rules, it seems appropriate that financing income imputed by those rules is brought into account when applying the EIFEL rules.

Excluded interest – extended to certain partnerships and lease financing amounts

The “excluded interest” election operates by removing elected amounts of interest from IFE and IFR and, therefore, from the EIFEL calculations. This results in no IFE to deny in the borrower entity, but also a loss of the IFR benefit in the reciprocal lender entity. In addition, the interest expense/income is not added back/deducted in determining ATI.

Significant changes have been made to this election, which was previously available only for interest on loans between two taxable Canadian corporations. In the November 2022 draft legislation, this has been extended to include situations where a partnership is the payer or payee, provided that each partner of the partnership is a taxable Canadian corporation and an eligible group entity in respect of the counterparty. For example, if the payer is a partnership, each partner must be an eligible group entity in respect of the payee (if the payer and payee are both partnerships, each partner of each partnership must be an eligible group entity in respect of each partner of the other partnership). For tiered partnerships, proposed ITA subsection 18.2(12) requires that, where a partner of a partnership is itself a partnership, the test should be applied on a “look-through basis” as though the partners of the upper-tier partnership were partners of the lower-tier partnership.

Due to the broadening of this rule and the transfer of excess capacity election, the term “eligible group corporation” in the original draft legislation has been subsumed into the existing term “eligible group entities.” The election has also been restricted from applying in situations where the payer is not a financial institution group entity, but the recipient of the interest income is a financial institution group entity. In addition, the election has been broadened to include “lease financing amounts,” which are deemed interest amounts required to be computed for certain leases (which are not excluded leases) for purposes of the EIFEL calculation; the computation uses a method which assumes that the leased property was instead acquired and financed by a deemed loan that was equivalent to the FMV of the leased property at the date the lease was entered into. Amendments have also been made to the administrative provisions in respect of the election, to take into account the extension of the rule to partnerships and lease payments.

PwC observes

Partnerships are often used as part of inter-group loss utilization strategies. The ability to exclude interest that exists between a partnership and a taxable Canadian corporation in the same group should enable groups that have various partnerships, or tiered partnerships, with loans to Canadian corporate entities to access the excluded interest election. However, there are still some areas to watch out for. The election will not be available if any partner in the partnership is an individual, a trust, a corporation that is not a taxable Canadian corporation, or a taxable Canadian corporation that is not an eligible group entity (e.g. if a minority interest is held by a person outside the group).

The extension of this election to lease financing amounts will simplify the application of the EIFEL rules in situations where leases (which do not fall within any of the categories of an excluded lease) are between two taxable Canadian corporations, or similarly in certain situations involving partnerships.

The restriction on amounts paid by a non-financial institution group entity to a financial institution group entity is curious, as this restriction appears to be reversed in the explanatory notes published by the Department of Finance. Finance describes this restriction as applying when amounts are paid by a financial institution group entity to a non‑financial institution group entity. Hopefully this discrepancy will be resolved in the final legislation.

Without significant amendments to how an excluded interest election can be made in the group context, the excluded interest election remains a potentially onerous election to make, given that there is a requirement to specify a particular debt and amount of interest, or a lease financing amount and the FMV of the leased property. The Department of Finance has provided some clarity that the debt balance to be provided in the election is the amount at the start and end of the year; however, this could still be a complex election for groups that wish to exclude a significant number of loans.

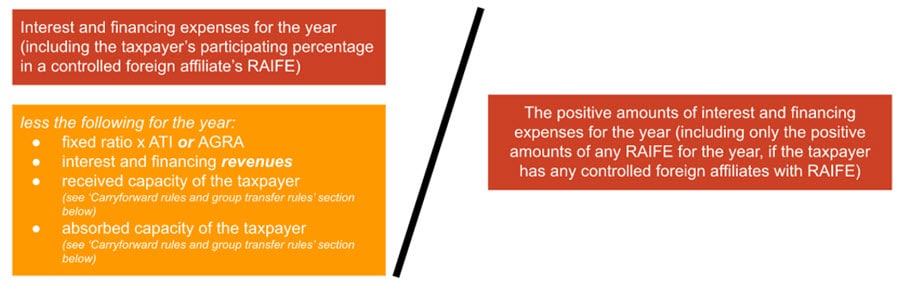

Determination of allowable interest and financing expenses in a taxation year

The EIFEL rules operate through a determination of a percentage of excessive interest and financing expenses in the main operating provision in ITA subsection 18.2(2). The November 2022 draft legislation includes some notable changes to this calculation, to accommodate new rules for relevant affiliate interest and financing expenses (RAIFE) and relevant affiliate interest and financing revenues (RAIFR) of controlled foreign affiliates. The revised formula is shown in the diagram below.

PwC observes

The main changes to this rule are to ensure that the ITA subsection 18.2(2) limitation proportion is appropriately calculated with the new inclusions to IFE and IFR for amounts in respect of controlled foreign affiliates.

Once calculated, the ITA subsection 18.2(2) denied interest percentage is then applied to various elements of the IFE definition, excluding those amounts which arise in a partnership or controlled foreign affiliate which are dealt with through separate provisions (ITA paragraph 12(1)(l.2) and clause 95(2)(f.11)(ii)(D), respectively). The definition of IFE is separated into amounts that increase IFE and those that reduce IFE. We would note that, in the earlier version of the rules, the ITA subsection 18.2(2) percentage did not apply to the amounts which reduce IFE, even though the denominator of the subsection 18.2(2) percentage included all IFE. This remains the case in these new rules; however, the revised denominator in the proportion now excludes these amounts that reduce IFE, meaning the percentage should now be applied to a like-for-like IFE amount leading to the taxpayer obtaining the benefit for the amounts that are reducing IFE.

Application of the EIFEL rules to controlled foreign affiliates

An important update to the EIFEL rules is that they now include specific provisions to apply them to controlled foreign affiliates (CFAs). The general approach the Department of Finance has adopted in applying the rules to CFAs is somewhat similar to the treatment of partnerships. Essentially, a Canadian taxpayer must include, in its own EIFEL calculations, its proportionate share of the IFE and IFR of its CFAs that are relevant in computing their FAPI. If a percentage of the taxpayer’s IFE is non-deductible under the rule in ITA subsection 18.2(2), the same percentage is applied to deny the deduction of IFE in computing the CFAs’ FAPI. The EIFEL rules do not otherwise apply in computing the FAPI or surplus balances of foreign affiliates, i.e. CFAs are not required to perform their own EIFEL calculations. This has been made explicit in the November 2022 draft legislation. Broadly this means that:

- each CFA of a Canadian taxpayer must compute its RAIFE and RAIFR – these are the amounts of IFE and IFR, respectively, which are relevant in computing the CFA’s FAPI (i.e. IFE and IFR that are relevant in computing active business income are generally not included in the Canadian taxpayer’s EIFEL calculations)

- the Canadian taxpayer's share of a CFA’s RAIFE and RAIFR (determined based on its “participating percentage” in the CFA) is included in the taxpayer's IFE and IFR amounts, respectively – these amounts are therefore included in determining the proportion of the taxpayer’s IFE that is non-deductible under the main EIFEL operative rule in ITA subsection 18.2(2) (rather than computing a separate EIFEL proportion at the CFA level)

- the taxpayer’s overall EIFEL proportion is then applied to the CFA's RAIFE amounts, deeming the same proportion of those RAIFE amounts to be non-deductible in computing FAPI (a similar rule applies for RAIFE of a partnership of which a CFA is a partner) – these rules effectively increase the amount of FAPI that is included in the Canadian taxpayer’s income

- the denied RAIFE of the CFA is added to the taxpayer’s indefinite RIFE carryforward balance (rather than a separate carryforward balance for the CFA) – similarly, any excess capacity generated from the inclusion of the CFA amounts in the taxpayer’s EIFEL calculation is an attribute of the taxpayer rather than the CFA

In determining the amount of a CFA’s RAIFR that gets included in the taxpayer’s IFR, a reduction applies for amounts deducted by the taxpayer as foreign accrual tax (FAT) in respect of the RAIFR. Although FAT can be deducted over a period of up to 5 years following the year of the related FAPI inclusion, depending on the year in which the foreign tax is paid, the RAIFR reduction is required to be made entirely in the year of the FAPI inclusion.

Other adjustments have been made throughout the draft legislation to reflect the inclusion of CFAs, including an amendment to the non-capital loss adjustment in ATI for the amount of current year FAPLs that relate to net RAIFE and amounts included in FAPI due to the EIFEL rules, reflecting the fact that RAIFE is instead now included in IFE for the taxpayer and therefore already factors into being an addback in determining ATI.

PwC observes

The application of the EIFEL rules to CFAs that have FAPI will add a significant level of complexity to the Canadian taxpayer’s EIFEL calculations. Similar to how the rules are intended to apply to partnerships, the addition of the rules for CFAs requires the Canadian taxpayer to look through to the detail of the interest and financing expenses and revenues of its CFAs.

Practically, the reduction of RAIFR in the FAPI year for FAT deductions taken in subsequent years could create a compliance challenge. Reducing the IFR in respect of a future FAT deduction also seems to exaggerate the current tax impact of the EIFEL rules, since the Canadian taxpayer must include the full FAPI amount in its taxable income for the current year (with the FAT deduction available only in the future year), but cannot benefit from the IFR (to the extent of the future FAT deduction) to create current year capacity for purposes of its EIFEL calculation.

Because the FAPI inclusion for each CFA will be determined using the taxpayer’s aggregated ITA subsection 18.2(2) percentage multiplied by the CFA’s RAIFE, there could be a mismatch between the CFAs that have this FAPI inclusion and the CFAs that pay foreign tax. Intercompany loans often have the effect of shifting income between CFAs for foreign tax purposes; the EIFEL rules can effectively reverse this shift for FAPI purposes. As a result, some CFAs could have FAPI, as a result of this new EIFEL rule, without foreign tax to generate FAT deductions, while other CFAs pay foreign tax without earning FAPI. This mismatch could prevent a taxpayer from having sufficient FAT deductions to offset the FAPI inclusion under the EIFEL rules, even if the overall foreign tax paid by CFAs on an aggregated basis exceeds 25% of the total FAPI.

With the extension of the EIFEL rules to CFAs, it seems desirable to have the ability to elect to exclude interest paid between two CFAs, or even interest paid between a CFA and its Canadian shareholder. However, the "excluded interest" election requires the payer and payee to be taxable Canadian corporations, or a partnership of such corporations. Hopefully the final legislation expands the “excluded interest” definition to include CFAs.

Group ratio rules

Canadian members of a group of corporations and/or trusts (and certain standalone entities) may jointly elect to have the group ratio rules apply. This election replaces the fixed ratio in ITA subsection 18.2(2) (30%, or 40% under the transitional rule) with a ratio based on the group’s net third-party interest expense to book EBITDA. The group ratio rule essentially allows taxpayers to deduct a greater percentage of IFE, where the group as a whole is bearing higher IFE as a result of its external debt.

To apply the group ratio rules, Canadian group members will be required to jointly elect into the regime with respect to the relevant taxation year. The election is required to be filed on or before the earliest filing due date of a Canadian group member for the year and must include an allocation of the group ratio amount to each Canadian group member. This allocated amount then becomes the group member’s interest expense deduction “room” under the EIFEL rules, rather than the fixed percentage of its ATI.

Consolidated group

To apply the group ratio rules, certain conditions must be met and some of these conditions have been amended in the revised draft legislation. Most notably, it appears that Canadian group members are no longer required to have the same taxation year end or the same tax reporting currency. In addition, there is no longer any restriction on financial institutions participating in the group ratio regime.

The rules for the group ratio are heavily dependent upon terms defined by international accounting standards. For this purpose, the November 2022 draft legislation has revised the list of acceptable accounting standards to also include the GAAP of the United Kingdom, European Union member states, European Economic Area jurisdictions, Switzerland, Brazil and Mexico.

The new rules also include the ability to make an amended or late election, or to revoke an election, if:

- it can be demonstrated to the Minister of National Revenue’s (i.e. the Canada Revenue Agency’s [CRA’s]) satisfaction that: (i) reasonable efforts were made to determine all amounts relevant in making the election, and (ii) the election is filed as soon as circumstances permit

- in the opinion of the Minister, it would be just and equitable to permit the election to be made, amended or revoked

PwC observes

Although the removal of the same tax reporting currency requirement is a positive development, no guidance has been provided as to how to convert relevant amounts between currencies.

The introduction of additional countries’ GAAP as acceptable accounting standards should make the process of considering whether the group ratio may be beneficial simpler for Canadian subsidiaries of foreign multinational groups whose ultimate parents are located in these jurisdictions.

The opening up of the group ratio regime to financial institutions should allow groups that are not primarily financial institutions (but which may have had some entities with activity that could have previously fallen into this definition in the draft rules) to apply the group ratio across their group as a whole. Although this may appear to be a significant change in tax policy, it would not usually be expected that financial institution groups would have a group ratio that exceeds the fixed ratio, given their high amounts of interest revenue.

The ability to late-file, amend or revoke a group ratio election is a welcome change and recognizes that the practical application of the group ratio rules may be complex in circumstances where entities have different year ends or may be required to perform calculations at an entity level for various entities at different times before the group ratio information is available. However, it should be noted that, if taxpayers wish to make an amended election, time is of the essence and it is ultimately a CRA determination as to whether the amendment will be accepted.

Group ratio calculation

The group ratio is generally calculated as follows, with these terms being derived from the consolidated financial statements of the group, with certain adjustments:

The original draft group ratio rules contained formulaic restrictions that would reduce the allowable group ratio in a somewhat arbitrary manner, if the group ratio would otherwise have exceeded 40% (for instance, the formulae would require an actual group ratio of 260% to permit an allowable group ratio of 100%). These restrictions have now been removed, meaning that the actual group ratio will be used to determine an electing group’s deduction room. However, if the GANBI for the consolidated group is nil or negative, the group ratio will be deemed to be nil.

The GANBI rules now allow taxpayers to elect to exclude fair value accounting adjustments. The election must be made jointly by all Canadian group members for the first taxation year to which they elect to apply the group ratio regime and it applies for that taxation year and any subsequent taxation year.

Changes have also been made to account for the exclusions from the EIFEL rules of IFE, and the related income, attributable to certain public-private partnership infrastructure projects. These amendments impact both GNIE and GANBI.

PwC observes

The removal of the arbitrary reduction formulae is a welcome change and could greatly increase the benefit of a group ratio election to those taxpayers who meet the conditions for the group ratio.

If considering the group ratio election, the fair value adjustment election will require careful scenario modelling to consider whether this election is beneficial – most notably, because the election is required to be made in the first relevant taxation year and then applies for all years thereafter. Thus, there is a one-time choice to be made as to whether to include fair value amounts in the group ratio formula.

Carryforward rules and group transfer rules

The EIFEL rules allow taxpayers to carry forward certain amounts from the current taxation year to later taxation years. Specifically, taxpayers can carry forward:

- excess capacity to deduct IFE, and

- denied (or restricted) IFE

In addition, the rules allow group entities to transfer excess capacity to other group entities.

Excess capacity

In the November 2022 draft legislation, the conditions for transferring excess capacity have been updated to enable eligible group entities with a different tax reporting currency to transfer capacity. In addition, the ability to transfer excess capacity has been expanded to certain “fixed interest commercial trusts” and financial institutions. Finally, explicit rules have been added for late or amended excess capacity transfer elections.

For financial institution group entities (or insurance holding corporations), the rules now enable the transfer of excess capacity, provided the transferee is also a financial institution group entity, insurance holding corporation or special purpose loss corporation. However, restrictions are placed on the transfer of excess capacity from financial institution group entities to insurance holding companies or special purpose loss corporations. According to the Department of Finance, the goal of these restrictions is to limit the transferred amounts to those necessary to give effect to certain “debt push-down” transactions within financial institution groups, while ensuring that the excess capacity is only used to support the deductibility of interest expense shifted into financial institution group entities, rather than related non‑financial institution group entities.

In the context of CFAs, excess capacity will only be an attribute of the Canadian taxpayer (i.e. there will be no separate attributes for the CFAs).

As with the original proposals, a taxpayer’s excess capacity does not survive a loss restriction event.

Restricted interest and financing expense (RIFE)

The main change to RIFE carryforward amounts is that they can now be carried forward indefinitely (rather than the 20-year carryforward originally proposed). RIFE carried forward will now also include any IFE which are denied in determining FAPI of a CFA of the taxpayer. A taxpayer’s RIFE carryforward will survive a loss restriction event to the extent that the interest is sourced to income from a business and the taxpayer continues to carry on the same business following the loss restriction event.

PwC observes

Allowing excess capacity transfers between entities with a different Canadian tax reporting currency is a welcome amendment providing additional flexibility in sharing excess capacity within a group. However, no guidance has been provided as to how to convert these amounts between currencies. Should a taxpayer be required to convert these amounts, presumably they would either convert the excess capacity of the transferor to the transferee’s tax reporting currency using the relevant spot rate for the last day of the transferor’s taxation year, or use the average rate for the transferor’s taxation year. Clarification from the Department of Finance on how the conversion should be calculated would be welcome.

The ability for financial institution group entities or insurance holding corporations to transfer excess capacity to other similar entities is also a welcome amendment for the financial services industry. However, the revised rule does ringfence any entities in this industry so that they can only share this capacity amongst themselves (subject to limited exceptions for certain debt push-down transactions). In addition, the introduction of the “fixed interest commercial trust” definition means that such capacity transfers are opened beyond corporations to certain non‑discretionary trusts resident in Canada, which may be helpful in groups involving multiple trusts and/or corporations.

The move to an indefinite carryforward period for RIFE recognizes that RIFE is a more difficult attribute to utilize than non-capital loss carryforwards. Whereas a non‑capital loss can be used in any future taxation year in which there is positive taxable income, the utilization of RIFE requires a future year with excess capacity under the EIFEL rules. Such excess capacity would typically arise only when: (i) there is a significant increase in ATI, such that the entity can deduct its IFE in that future year and start to utilize this previously denied interest, or (ii) a refinancing event takes place, which significantly changes the proportion of IFE to ATI in a future year. The interaction between RIFE and non-capital loss utilization will be important for taxpayers to consider for tax accounting purposes. For instance, the EIFEL rules could cause a change in the recognition of tax assets for accounting purposes, such as in a situation when a business is accumulating RIFE and has historic non-capital losses that may not be recognised as a deferred tax asset for accounting purposes (or that have a full valuation allowance recognized against a potential deferred tax asset) and the historic non-capital losses will now be utilized to offset the increase in taxable income due to the EIFEL restrictions. Whether a tax asset can be recognized for a RIFE carryforward balance may be difficult to determine due to the unpredictability of its future utilization and will likely require EIFEL calculation projections for future years.

Although RIFE sourced to income from a business generally does not expire on a loss restriction event, provided that the taxpayer continues to carry on the same business, interest expense could often be sourced to income from property, which could cause such RIFE to expire (i.e. it would never be able to meet the “carrying on a business” requirements). In certain circumstances, this may not be an equitable result. For instance, when a Canadian holding company incurs interest on funds used to acquire shares of another Canadian company with active business operations and, for non-tax reasons, the companies do not amalgamate, any RIFE (at the Canadian holding company level) would be sourced to income from property (i.e. the shares of the operating company). Had the Canadian holding company and operating company amalgamated, the RIFE of the amalgamated company could have been sourced to income from the business. The Department of Finance should consider whether some form of relief should be available in these circumstances, such as providing that interest incurred to indirectly earn income from a business should be sourced to the business for purposes of the loss restriction event rules.

Anti-avoidance provisions

The three separate anti-avoidance provisions for IFE and IFR in the original draft legislation have been replaced with a single anti-avoidance rule. The new draft anti‑avoidance rule primarily excludes amounts from IFR in three situations, if:

- an amount in respect of the IFR amount is deductible in computing FAPI of a non-controlled foreign affiliate of the taxpayer (e.g. this rule would deny IFR treatment for interest revenue, when the interest expense is deductible in computing FAPI of a non-controlled foreign affiliate)

- the IFR amount is received from a person that does not deal at arm’s length with the taxpayer and is an excluded entity, an individual or a financial institution group entity (if the taxpayer itself is not a financial institution), or from a partnership of which any of the preceding types of persons is a partner

- one of the main purposes of a transaction or series of transactions is to increase either IFR or an amount that reduces IFE, when certain conditions apply

PwC observes

The anti-avoidance provision with respect to IFR is distinctly narrower than in the original draft legislation, with one of the consequences being that it has removed concerns around whether interest revenues on all loans to non-arm’s length non-residents (including foreign affiliates) would be excluded from IFR. The more limited anti-avoidance rule denies IFR additions for amounts that are deductible in determining FAPI of a non-controlled foreign affiliate.

Notwithstanding this narrower scope, the explanatory notes to the November 2022 draft legislation mention that the general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR) may apply in situations that are not covered by these specific anti-avoidance rules. Thus, taxpayers should still be aware of the risks inherent in transactions that may result in increasing an amount of IFR or reducing an amount of IFE.

Areas of the EIFEL rules with limited changes

While there have been significant changes to the EIFEL rules in a number of areas, some areas appear to have had only minor amendments, specifically:

- Ordering of the EIFEL rules – the order in which the EIFEL rules apply remains the same and the EIFEL rules will apply after all other interest deductibility rules have been applied

- Pre-regime election – the pre-regime election (to carry forward excess capacity generated in the three years before the EIFEL rules take effect) remains largely unchanged, although it has been revised to make it accessible to fixed interest commercial trusts; the group net excess capacity calculation for pre-regime years has also been amended to align it with the revised rules for transfers of excess capacity among financial institution group entities

- Lease financing amounts – there have been no significant changes to what should be considered an excluded lease, or how to calculate a lease financing amount where a taxpayer is required to determine a lease financing amount, under the EIFEL rules

PwC observes

Before undertaking EIFEL calculations, it will be important for taxpayers to understand their positions for interest deductibility under the transfer pricing, general interest deductibility, hybrid mismatch arrangement2 and thin capitalization provisions.

Taxpayers should note that the pre-regime election must be filed by the tax return filing deadline for the first taxation year that is subject to the EIFEL rules; for calendar year taxpayers, the deadline is likely to be June 30, 2025. However, up to three years of EIFEL calculations for these pre-regime years may be needed to understand whether this election could be beneficial, so this modelling exercise should not be delayed.

Next steps

The deferral of the commencement date of the EIFEL rules is a welcome development for taxpayers with taxation years starting between January 1, 2023 and September 30, 2023; however, the significant complexity remaining in the draft EIFEL rules should be considered now, to understand the overall impact on existing interest deductions in their businesses. These taxpayers should also note that the 30% fixed ratio will take effect in the first EIFEL year (subject to the availability of other relief mechanisms within the rules, such as the group ratio), rather than the 40% transitional ratio.

PwC observes

Modelling that has already been undertaken should be updated for the revised draft legislation – notable areas that may need to be revisited include calculations with respect to CFAs, as well as the new ability to share excess capacity among taxpayers with different tax reporting currencies and to make the excluded interest election for loans between taxable Canadian corporations and certain partnerships.

The takeaway

For groups with CFAs earning FAPI, the revised rules have significant amendments that could impact the EIFEL position of the Canadian taxpayer. As a result, we would recommend revisiting any modelling undertaken to date to consider the impact of including CFAs in the Canadian taxpayer’s calculations.

The opening of a second consultation period through to January 6, 2023, demonstrates the complexity of these rules and importantly, provides taxpayers with a further opportunity to express any concerns or uncertainties as to how the rules might apply in their specific circumstances. Although the application of the rules has been deferred, taxpayers should use this additional time to prepare for their impact and consider restructuring their financing arrangements, to limit the adverse implications of the EIFEL rules.

1. See our 2022 Federal Budget analysis.

2. See our Tax Insights “Canada introduces first package of hybrid mismatch rules.”

Contact us

National Growth Priorities Markets Leader, Partner International Tax, PwC Canada

Contact us