Intangibles: Tax Risks and Opportunities for Multinational Groups

Mohamed Serokh, PwC Middle East Tax Partner, talks about success and how it comes from valuable so-called core ‘intangibles’, like brand, technology patents, know-how, first mover network value and other high value non tangible assets.

Companies like Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, Facebook and Amazon are among the largest multinationals in the world by market value in 2018. They all share a success story but that is not the only thing they have in common. Their success comes from valuable so-called core ‘intangibles’, like brand, technology patents, know-how, first mover network value and other high value non tangible assets.

Intangibles are seen as the main driver of value creation and a major source of sustainable competitive advantage for a majority of multinationals and now more so than ever! Technological changes and the digital revolution have facilitated this process and enabled intangibles as key profit drivers.

All companies own some type of intangibles, but do all companies know what intangibles they possess and how to manage them? Do they strategically think which intangibles to develop or acquire, how to develop these and what resources to utilize? Have they considered the tax implications around them? Let’s discuss…

Intangibles and tax

Just what are intangibles and what is there relevance to tax?

In simple terms, intangibles are valuable assets with no physical substance. A key category of intangibles is intellectual property (IP), where the creator’s or inventor’s ownership rights are protected under law. This entitles them to earn economic returns or recognition for this IP.

Patents, copyrights, designs and trademarks are common types of IP. However, other examples of intangible assets also include customer relationships, trade secrets and business reputation.

The taxation of intangibles can be seen from two traditional dimensions of tax law: (i) domestic law; and (ii) treaty (international) law.

From a domestic law perspective, some of the key taxation issues are the deductibility of costs in the development of intangibles, the treatment of capital expenditures, taxes on royalty payments, withholding taxes and the arm’s length price of payments related to intangibles.

Tax treaties typically deal with the allocation of taxing rights to the countries of the parties to the transaction concerning intangibles. Depending on the treatment of the income from the intangible (royalty or not), taxing rights are allocated accordingly between the countries.

In the case of a royalty payment, typically the country of the payer of the royalty withholds tax, while in the country of the recipient, they could obtain some type of a double taxation relief depending on the treaty between the payer and recipient countries.

On the other hand, in the case of intangibles other than IP which are not classified as royalties, there would most likely be no withholding tax in country of the payer but this income would only be taxed in the country of the recipient of the income.

This provides an incentive for multinationals to move intangibles to low-tax jurisdictions.

But what is the role of transfer pricing and how does it impact intangibles?

Transfer pricing and intangibles

In the case of intangibles, transfer pricing issues can arise when multinationals develop, transfer, acquire or exploit intangibles. For transfer pricing purposes, an intangible is “something which is not a physical asset or a financial asset, which is capable of being owned or controlled for use in commercial activities, and whose use or transfer, would be compensated had it occurred in a transaction between independent parties in comparable circumstances” in accordance to OECD guidance.

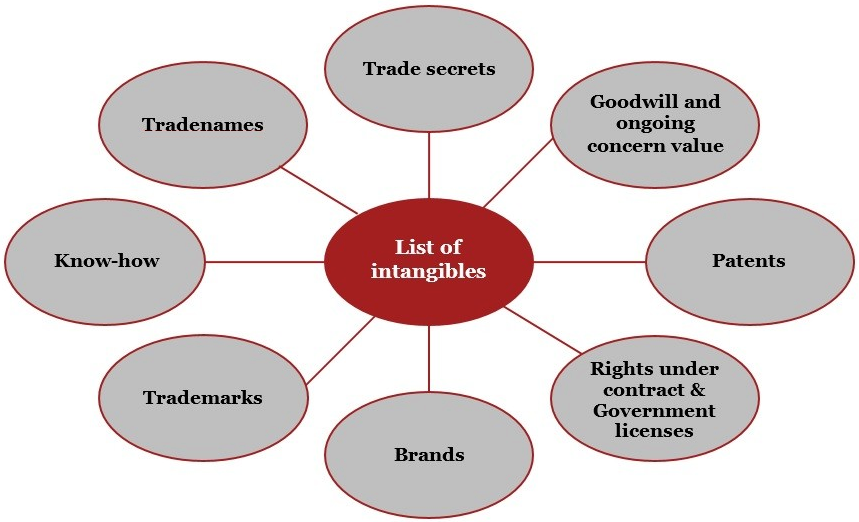

As you can see, the definition of intangibles for transfer pricing purposes is neither too narrow nor too broad and does not rely on typical accounting, legal or tax definitions. The diagram below shows some indicative intangibles from a transfer pricing perspective.

Figure 1: Types of Intangibles relevant to tax and transfer pricing

However, market specific circumstances and group synergies that may contribute to the income earned by a multinational, are not intangibles themselves for transfer pricing purposes, as it would be very difficult to attribute ownership to any particular entity in a group.

DEMPE – A recent OECD concept

Let us imagine, we have a number of related parties in several countries that develop and exploit an intangible. How do we allocate the income from the exploitation of the intangible to the involved parties?

In its publication on Action 8 of the Base Erosion & Profit Shifting projects (2015 to 2017), the OECD has introduced the concept of Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection and Exploitation functions – DEMPE – of intangibles. With the introduction of the DEMPE concept, the OECD aims to ensure that the allocation of economic returns from the exploitation of intangibles will be based on the relative contribution of each party to the Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection and Exploitation of the intangible. Specifically, DEMPE functions are defined as follows:

Figure 2: OECD DEMPE Functions

With the adoption of DEMPE functions, the OECD contemplates focusing on entities that may not be legal owners of the intangibles but have made significant contributions to the creation of the intangibles that do not receive their “fair share” of income. Specifically, these entities may have performed functions and undertook risks that were adding value to the creation of intangibles and for that, based on the DEMPE approach, they should be compensated accordingly.

Is the DEMPE concept changing the tax landscape on intangibles?

Prior to the adoption of the DEMPE approach from the OECD, it could be argued that the legal owner of an intangible such as a trademark or a patent should be at least partially entitled to the economic returns from the exploitation of the intangible.

With the introduction of DEMPE, the economic returns resulting from the use of an intangible should be allocated to entities that perform and control the value creating DEMPE functions.

Legal ownership, combined with the identification and compensation of relevant functions performed, assets used and risks assumed by all relevant parties, provides the analytical framework for identifying the arm’s length remuneration that the involved parties are ultimately entitled to. This implies that the legal owner of the intangible is entitled to the economic returns only in the case that they also perform DEMPE activities.

Furthermore, in case that the legal owner does not perform some key activities within the DEMPE approach, the deductibility of the relevant expenses for the development of the intangible could come under review during a tax audit.

Figure 3: The impact of DEMPE on Legal Ownership

The implication for multinationals?

The DEMPE approach has already started to impact the way multinational groups structure the development and exploitation of intangibles considering tax implications.

Multinationals need to follow a number of steps for analyzing intra-group transactions involving intangibles, including:

- Identifying intangibles at stake, the relevant contractual arrangements and the relevant parties involved in the creation of the intangibles;

- Identifying the functions performed, assets utilized and risks involved in the framework of the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation of the intangibles;

- Reviewing the consistency between the contractual arrangements and conduct of the involved parties for the creation of the intangibles; and

- Allocating the economic returns from the exploitation of intangibles between the involved parties on the basis of the functions performed and the risks associated with DEMPE functions.

These steps are simply illustrated in the following figure.

Figure 4: Steps in the Treatment of Intangibles for Tax & Transfer Pricing Purposes

In undertaking the above steps, multinational groups need to consider:

- Which members of the multinational provide substance (DEMPE functions) related to the intangible?

- Which members provide funding and other assets in relation to the creation of intangibles?

- Which members assume the various risks associated with the creation of intangibles?

But how can transfer prices for intangibles actually determined?

Intangibles represent unique and valuable assets that pose substantial challenges to price with precision. In the transfer pricing world, there is often a lack of “comparables” i.e. comparable transactions relevant to the intra-group transactions concerning intangibles. As intangibles are becoming more complex and more valuable, identifying comparable transactions becomes increasingly difficult.

The OECD has issued guidance to determine an arm’s length price for transactions involving intangibles. The guidance establishes the following key points:

- Consideration should be given to both parties involved in the transaction. Tax authorities will most likely consider a “one-sided” comparability analysis as insufficient to evaluate the transaction.

- Pricing intangibles on a cost basis is generally discouraged. Most likely methods utilizing comparable transactions will be the most reliable if such transactions can actually be identified. If not, some form, of profit split might be more appropriate.

- Where reliable comparable uncontrolled transactions are not available, valuation techniques can be seen as a useful tool in evaluating intra-group transactions involving intangibles.

Conclusion

Intangibles are of critical significance for multinational groups from a business, operational and tax perspective. In the tax and transfer pricing sphere, the introduction of the DEMPE approach is fundamental and helpful to businesses address the tax impacts of intangibles. With this approach, multinationals should be able to better align the functional and risk profile of their entities with their profitability. Practically, this implies that if there is more substance in a jurisdiction, then, other things being equal, more profits should be attributed and more tax paid in these jurisdictions. Conversely, businesses undertaking DEMPE functions in low tax or no tax jurisdictions can justifiably attribute greater profits from intangibles to these jurisdictions and pay less tax.

In today’s world, with major global and local challenges, is the OECD approach and DEMPE a tax risk or an opportunity for businesses? The answer is that it’s both!

To capitalize, multinationals need to formulate a holistic approach to their operating and tax model and the consequent impact on their tax strategy in regards to intangibles having regard to the new OECD concepts on intangibles!