Part 2 - Intangibles: Only through the Functional Analysis door can opportunities truly knock

May 13, 2018

Mohamed Serokh PwC Tax Partner & Middle East Transfer Pricing Leader, PwC Middle East - Author

Baback Randjandiche PwC Tax Senior Manager, PwC Middle East - Co-Author

Part 1 of our Intangibles we discussed the relevance of intangibles to tax, and specifically, introduced the OECD’s DEMPE framework in the transfer pricing analysis of intercompany transactions involving intangibles. DEMPE stands for Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection and Exploitation, and was meant to be a clarification to the existing guidance on intangibles.

Part 2 of our Intangibles discussion examines some critical questions on the application of the DEMPE framework, and the importance of a functional analysis to overcome conceptual challenges of this framework.

As a tax practitioner works through the implications of the OECD guidance on intangibles, one might ask the following questions: Does each letter in the DEMPE acronym represent a significant value driver that is entitled to returns derived from intangibles? For example, does the “D” in the DEMPE framework imply that we are to allocate intangible returns to entities that are engaged in Development activities, even when these activities are contractually structured as an intra-group service? Do functions now trump actual risk taking?

As the activities designated under the DEMPE framework are bound to be performed across more than one entity, would this elevate the profit split method to the default method of choice? How does outsourcing figure in all of this? The answer to many of these questions lies at the door of the functional analysis, so let’s discuss …

The context: DEMPE and the importance of the functional analysis

The first step in understanding DEMPE is to take a step back and remember the context in which the DEMPE framework arose.

In 2012, the OECD and G20 launched the Base Erosion & Profit Shifting (BEPS) project, and which aimed to counter perceived international tax avoidance techniques. It was the OECD’s view that the lack of substance that existed in some of the pre-BEPS tax structures were founded in an incorrect delineation of the inter-company transactions, or in some cases, an incorrectly performed functional analysis (and characterization) of intercompany transactions. Its guidance therefore naturally focused on clarifying how to perform a functional analysis correctly. The DEMPE framework can be seen as part of that clarification.

Pre-BEPS: Functional analyses founded on contractual allocation

At the core of the application of the arm’s length principle (ALP), is a review of the important characteristics of an intra-group transaction. The most operative component of this review is the so-called Functional Analysis (FA), which maps out the functions (such as manufacturing), risks (such as product default risk) and assets (such as machinery and know-how) of the participating entities in the intra-group transactions.

The importance of the FA is grounded in the fact that a company’s profits are understood to be essentially driven by those three broad categories of factors. When a company performs more functions, or takes on more risk, or employs more assets than another company that is otherwise comparable, it can expect to receive a larger remuneration than that comparable company.

In the pre-BEPS era, functions were commonly thought of as activities performed by people, and therefore firmly anchored in the entities that employed those people, whereas risks could be allocated per contract, and were therefore much more mobile.

This mobile nature of risks led to the proliferation of tax structures where the location of risks could be divorced from the location of people, while seemingly not violating the ALP.

In line with the ALP, in many cases, entities actually bearing risks (i.e. providing the capital to cover the risks) were branded the entrepreneurs of the group while other entities were characterized as mere service providers to the entrepreneurs, and therefore entitled to no more than a routine remuneration for their services.

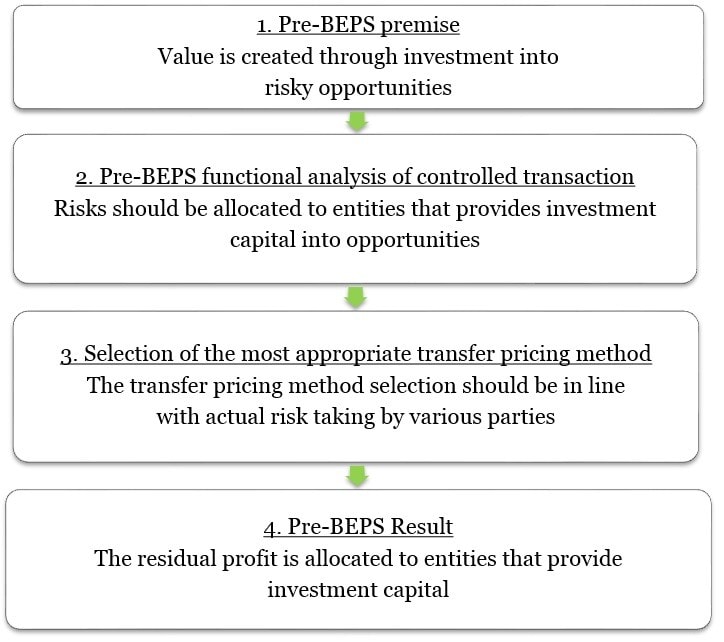

Figure 1 below shows the typical transfer pricing analysis steps as regards to risk allocation, from premise to result in many pre-BEPS cases.

Post-BEPS: Risk follows risk control functions

Through the BEPS project, the OECD has now taken the position that the location of risks cannot be a mere matter of contractual agreement between entities of the same group, without regards to where decisions are actually made.

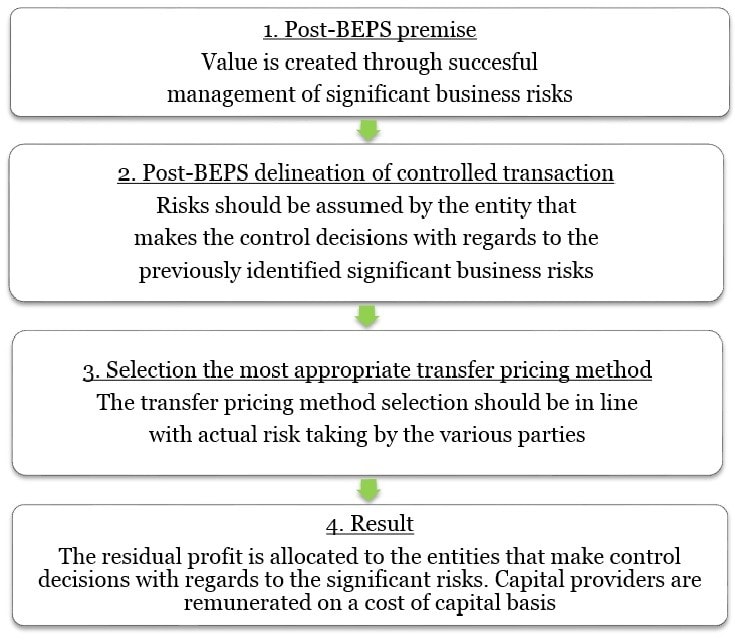

The transfer pricing results should still be in line with actual risk taking, but the actual risk taking on an investment should be assumed by the entities that made the important control decisions with regards to investments, rather than by default to the providers of capital.

When a transfer pricing analysis is then performed along these principles, with the risks correctly allocated, the resulting profit allocation should be in line with the substance of the structure.

Figure 1: Pre BEPS allocation of risk and profit in many cases

Figure 2: Post-BEPS allocation of risk and profit

The importance of the issue of ‘risk’ to DEMPE

With the above context in mind, we can tackle some of the common misconceptions surrounding the DEMPE framework.

One common misconception is that DEMPE is all about activities, because each of the letters in the acronym designates an activity. It is not however, in the same way that a functional analysis is not just about functions. A functional analysis typically looks at assets and risks, in addition to functions.

The DEMPE framework does not negate the requirement of doing a full functional analysis. It merely highlights to the tax practitioner the importance of doing the functional analysis throughout the complete intangibles value chain, which is what the DEMPE framework represents. And so rather than doing away with a traditional functional analysis and replacing it with some sort of activity-centric DEMPE analysis, the DEMPE framework ensures completeness of the functional analysis.

Another common misconception is that development, enhancement, etc. activities each command at least a portion of the intangible returns, on account of these activities being highlighted in the DEMPE framework.

In this interpretation, the DEMPE acronym is regarded as an across the board confirmation by the OECD that all entities involved in such activities are to be treated as adding significant value to the intangible, and are therefore entitled to intangible returns. A licensee for example, should be allocated some intangible returns, because, so the reasoning goes, it exploits the intangible (the second “E” in DEMPE), and thereby adds value/ maintains it.

This is incorrect. Activities as such do not command intangible returns. DEMPE doesn’t negate the general point that profit should be allocated to entities assuming significantfunctions and risk, and these should be assumed by entities that perform the asset and risk control decision functions. To the extent that the licensee does not perform any asset and risk control functions with respect to the exploitation of the intangible, it may not be entitled to intangible returns. It is the entity that decides on how the intangible should be exploited that should earn the intangible returns, e.g. such decisions might relate to whether the intangible should be sold or licensed out, under which terms, how the license risks will be managed going forward, etc. Yes, there is a focus on substance, and therefore on people, and therefore on functions. But the important functions are clearly identified as the control decision making functions over significant risks and the asset itself.

The Profit Split Method (PSM) by DEMPE backdoor default?

As the DEMPE activities are bound to be performed by more than one entity, it is tempting to conclude that all such entities are entitled to a piece of the intangible pie, and that therefore the PSM is the new default method when dealing with intercompany transactions that involve intangibles.

This misconception maybe largely based on the above misconceptions, i.e. the idea that the DEMPE framework focuses on activities at the expense of risk. That said, the use of the profit split method is likely to increase, as even asset and risk control decisions can proliferate in a group.

A Consumer Products Example

Sublime is the parent company of a group engaged in the manufacture and marketing of consumer products. Its main customers are large retail chains. Its marketing targets end consumers. It has a well-established brand in most countries of the world. A decision is made to enter a new geographical market, Country X, where the brand is little known. A new subsidiary Company X is set up. Sublime sets out the marketing strategy and bears the costs, which mainly consist of nationwide advertising and securing top shelf space at retailers along with in-store promotion campaigns. All trademarks are registered and Company X provides support in the matter when requested.

Country X has historically struggled with food safety standards and the main attraction of the brand to consumers in Country X turns out to be its perceived safety record. All food safety risks are managed by Sublime through its raw materials sourcing and its production and storing activities. Products in Country X are stored following detailed instructions from Sublime. A relatively high retail price is perceived to be a reflection of Sublime’s high food safety standards. A detailed functional analysis shows that Company X is a limited risk distributor. The controlled transactions between Sublime and Company X is the purchase of goods from Sublime so as to provide it with a modest margin on sales, which has been set with reference to the margin that comparable companies earn.

After a successful introduction period, mainly driven by initial consumer curiosity, sales stall and profits drop. Sublime continues to support the brand through marketing. Company X management understands that the brand’s main issue is its lack of adoption of local tastes, and the lack of regular introductions of new products into the product range. Sublime’s competitors in Country X bring out new products on a regular basis.

Company X takes the initiative to study local preferences, study local trends, and suggest new flavors to the group’s development team in the parent company. Sublime does not interfere in the process other than ensuring that the new products do not harm the Sublime brand, and it manages the actual technical development aspects of the new flavors. Furthermore, Company X suggests significant reductions in the retail prices across all products. This is rejected by Sublime, on the basis that it would position the brand too close to other brands with a weaker reputation in the market. As part of the corporate approval process, Company X draws up projections and budgets, and reports these to Sublime for financial feasibility purposes. It purchases inventory from Sublime on the basis of those projections. After a regional test phase, the new products are rolled out nationally. Sales pick up and profits recover. Company X continues to develop new products and make decisions with respect to the development, marketing and sales of these local products. The value of the brand as a whole in Country X benefits from the presence of these innovative products in the portfolio. Due to administrative ease, the group continues t0 remunerate Company X as a limited risk distributor.

Tax audit challenge

Upon tax audit in Country X, the tax authorities accept the delineation of the purchase by Company X of the first generation products as a limited risk distribution arrangement. With respect to the locally developed products however, the tax authorities may argue that the transactions should be accurately delineated as the provision of contract development, manufacture and logistics services by Sublime to Company X and that Company X should be the residual claimant on profits, after having remunerated Sublime for its services. The tax authorities’ functional analysis emphasizes Company X’s valuable contributions in terms of new product ideas development, and they argue that the marketing risks of the new products should have been allocated to Company X, as they are truly in control of those risks. The local tax authorities believe that Company X should be recognized as the true economic owner of the brand as far as locally developed products are concerned.

The Group’s defense strategy

Sublime may decide to challenge that assessment with a DEMPE analysis of its own, which points out the following:

- Due to its proximity to the local market, localizing the Sublime product portfolio by suggesting new flavors was part Company X’s general brief from the start. As such it acted under direction of Sublime, which had discretionary control over whether the new products were going to be added to the portfolio or not. Previous market penetrations in other geographic markets followed the same process of starting off with the core offering, and then expanding with localized products.

- Product innovations by Company X, even though successful, were derivative, rather than innovative. All new flavors were based on existing product offerings of competitors. The success of the new products were a reflection of the reputation of the brand combined with flavor profiles that were well known locally. This also explains why Sublime ended up accepting most of Company X’s suggestions.

- The Sublime brand’s main attraction in country X is still based on its perceived superior safety track record. Those risks are completely controlled by Sublime, including for the new products, though its manufacturing and logistics expertise.

- The initial local advertising during the test phase might not have been successful if not for Sublime’s continued commitment to the market, as apparent in its national advertising efforts. As such, the brand and existing products supported the new products.

- Not all flavors can be successfully incorporated into the Sublime products. As such, development risks, including the decision to discontinue development efforts, were under the control of Sublime.

A quick resolution?

After considering the tax payer’s defense, the local tax authorities decide that their initial characterization of Sublime as a contract service provider to be too aggressive. On the basis of the OECD updated guidance, the tax authorities feel that they have grounds to allocate (some of) the marketing and sales risks to Company X.

Given the diverging views of the taxpayer and the tax authorities, the outcome of the audit might be a higher margin for Company X on the locally developed products, or even a PSM. In the case of a PSM, the discussion would likely focus on the relative value of local product innovations versus the more established aspects of the brand.

This example illustrates:

- Intra-group transactions involving intangibles do not necessarily require separate payment, or a separate functional analysis, for the intangible;

- Even functional analyses of intra-group transactions involving intangibles focus on risk allocation. The above example centered on risks in the areas of development, enhancement, protection and exploitation;

- There is an increased scope for the use of the PSM;

- DEMPE and BEPS more generally has shed some light on how risks are to be allocated but it has also considerably complicated the process. More controversy is likely to occur because of a perceived occurrence of asset and risk control decisions in its jurisdictions.

- Satisfactory resolutions of transfer pricing disputes are going to require a detailed understanding of the industry and the value drivers, and a detailed understanding of who does what.

Conclusion

A misconception could arise such that tax practitioners perceive that the DEMPE framework represents an activity centered template that, when applied in line with the OECD guidance, almost always results in a PSM. However, the issue of risk assumption is certainly not out of the picture when dealing with intangibles. To the contrary, most if not all examples in the appendix to the chapter on intangibles in the OECD Guidelines focus on asset control and risk taking. That is not a coincidence. Decisions on assets and risks are very much at the center of any tax analysis involving intangibles.

BEPS has also necessitated thinking that risks are not necessarily allocated to the providers of funding or capital, but to the entities that perform risk control decisions. This general clarification applies to intangibles also.

In addition, the functional analysis for intangibles is further clarified by including a high level and general description of the intangibles value chain: the DEMPE framework. Each of the letters in the DEMPE framework do not represent a function per se, but rather a step in the typical value chain involving intangible assets. The bottom line as far as managing tax risks and opportunities? As far as DEMPE is concerned, it all lies at the door of the Functional Analysis … Just knock very hard!