National Visions

Planning for the future

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, which has just hit the halfway mark from its announcement in 2016, provides a powerful framework for reshaping its economy. It encapsulates a drive to reform and diversify the economy, rebalance government finances and invest in transformative projects.

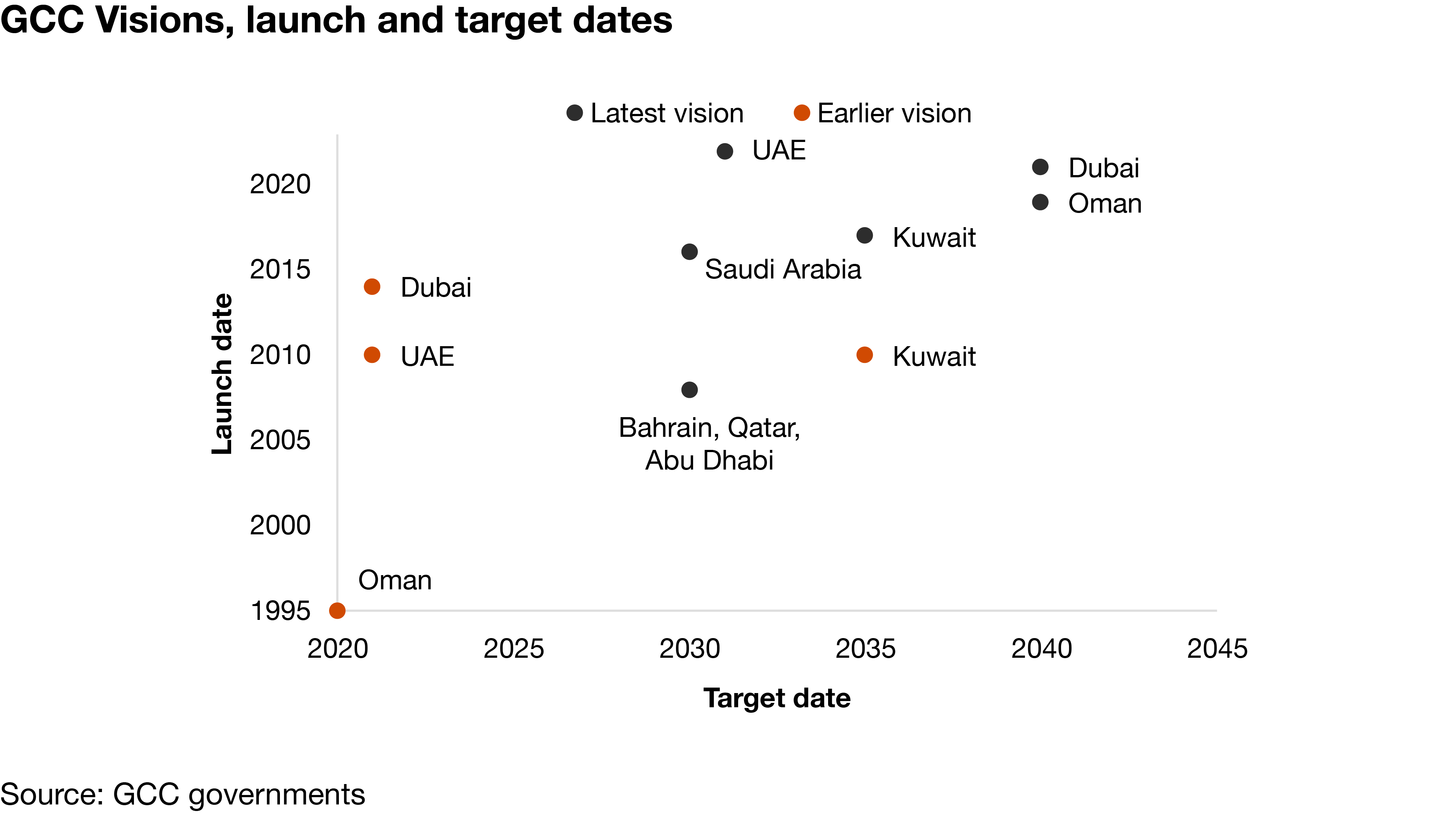

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 is only the latest in a series of these strategic national transformation plans developed across the GCC. Oman started the trend in 1995 with its Vision 2020, which laid the foundation for Vision 2040, developed under the leadership of HM Sultan Haitham shortly before his succession. In between the two Omani visions, the other GCC states all followed suit with their own long-term strategies, notably in 2008 when Bahrain, Qatar and Abu Dhabi each launched 2030 visions at the peak of that economic supercycle. The UAE’s first vision, launched in 2010, set its sights on its Golden Jubilee year in 2021 and was supplemented a few years later with a National Agenda, which added KPIs to track progress, and has now been succeeded by “We The UAE 2031”, and an even broader plan looking out to the centenary in 2071 including 50 projects to frame the next half-century of development. In addition, the UAE and its emirates have developed many long-term plans and strategies for specific economic sectors and emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence.

The GCC states are especially well placed to make and implement long-term plans for two key reasons. Firstly, they have substantial financial resources to direct to their objectives and secondly, their political systems result in continuity in leadership to see them through.

Common themes and special elements

The vision documents vary significantly in length. Abu Dhabi’s is nearly 150 pages in length whereas Qatar’s is fewer than 5,000 words, although the details of its implementation have been devolved to medium-term National Development Strategies, with the first two totalling over 500 pages and a final one for 2023-30 due to be released soon.

More recently the National Visions have also evolved more into multimedia endeavours, providing the country with a motivating framework and organising principles for national development, rather than a single linear document. The initial Saudi Vision 2030 statement, for example, is fairly brief, providing broad pillars of focus, including “Ambitious Nation”, “ Thriving Economy” and “Vibrant Society” and some performance targets for each. These were subsequently expanded into dozens of specific objectives and quantified targets, and sub-sector initiatives such as the Health Sector Transformation Programme. New projects have also subsequently been added as part of “Vision Realisation Programmes”, such as NEOM and the Saudi Green Initiative, which have become synonymous with Vision 2030. Saudi Arabia has also been advancing the Vision across government through regular reviews, both internal and published, including the five-year assessment. Other states also have mechanisms to assess progress, such as Oman’s Vision 2040 Follow-up Unit.

The visions have many commonalities but also some specific elements that are unique. The areas of common focus on the economic side include non-oil diversification, improving infrastructure, advancing digitalisation, creating a competitive business environment and equipping nationals with skills for productive jobs in the private sector - such as Saudization and Emiratisation. Country specifics include Kuwait’s emphasis on developing its lightly populated north – facilitated by the construction of a causeway over Kuwait Bay—and Saudi Arabia’s target of more than tripling its capacity to welcome Hajj and Umrah pilgrims. While all the visions primarily focus on the welfare of the citizen population, several also include socio-economic outcomes for expatriate residents in their objectives, notably Bahrain.

Good performance on some measures, with room for improvement in others

Many of the visions have quantified KPI targets for economic indicators against which their performance can be assessed. However, these targets should be carefully calibrated as some can be significantly affected in individual years by volatility in oil prices or other one-off factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or events like the FIFA World Cup or World Expo. Therefore, while it is useful to look at performance against the KPIs, this is only one part of assessing the relative success of the visions. It is also difficult to compare success between GCC states because most of their visions use different indicators and target years.

Abu Dhabi has made significant progress in diversifying its economy, with non-oil GDP reaching a 59% share in 2021, up from 41% in its baseline of 2005 and close to its 2030 target of 64%. However, it has been less successful in diversifying government revenue. It does not disclose non-oil revenue directly but combining IMF Article IV estimates for overall UAE oil revenue with Abu Dhabi’s most recently disclosed fiscal outturn in 2020 suggests that non-oil revenue was only about 28% of the total, far below its 2030 target of 49% and only slightly above its 2005 baseline of 23%. The rollout of corporate income tax this year will help somewhat but these effects are likely to be felt only in 2025 and beyond.

There are some areas of outperformance. In Saudi Arabia, female participation in the workforce has surged to 36% as a result of social reforms and job creation, already far ahead of its 2030 target of 30%. It has also made progress in some indicators related to reforms and investments, including rising to 38th in the Logistic Performance Index, up from 49th in the baseline and mid-way to the target of 25th. It has also made significant improvements in accelerating SME growth, with the targets to increase in loans to SMEs as a share of overall bank lending and increase the representation of micro- and small-cap companies on Tadawul (the local stock exchange) being achieved in 2020. SME Bank, which aims to bridge the financing gap for SMEs and is funded by the Saudi National Development Fund, also began its operations in December 2022.

However, further progress could be made on other indicators. FDI was under 1% of GDP in 2022, well below the 2030 target of 5.7% and even below the baseline level. That said, although public investment has been the main driver during the first half of the Vision’s implementation period, FDI may follow in the second half. Similarly, private sector GDP was 39% of the total in 2022, below both the target of 65% and the baseline, although that was distorted by an unusually strong year for oil. Meanwhile, non-oil GDP in 2022 was 15% larger in real terms and 28% in nominal terms compared to the 2015 baseline.

Visions of sustainability

The period in which these visions were created has indeed been one of economic reform and diversification in the region. While they have undoubtedly played a role in this process, there has also been plenty of transformation and innovation outside of their main framework.

One example is the recent drive towards decarbonisation of domestic economies (excluding exports). Although sustainability is mentioned in most visions, the majority of target-setting and activity has taken place more recently. The GCC’s experience of planning and implementing National Visions adds further credibility to their efforts to respond to the energy transition, including their net-zero targets between 2050 and 2060. They are already making rapid progress towards these objectives, including through the roll-out of large quantities of solar generation capacity in most GCC states, with more announcements likely with COP28 on the horizon. Moreover, the reality of the energy transition, while presenting new economic opportunities in the region, increases the impetus to make progress in implementing other goals under the National Visions.

In an era of rapid social, technological and ecological change, the ability to develop and implement national economic visions, as well as the agility to adapt these in a fast-changing world, are important strengths. Continued support and commitment by senior leadership, as well as stronger economic growth should provide the necessary momentum to achieve these visions.

Contact us

Richard Boxshall

Global Economics Leader and Middle East Chief Economist, PwC Middle East

Tel: +971 (0)4 304 3100