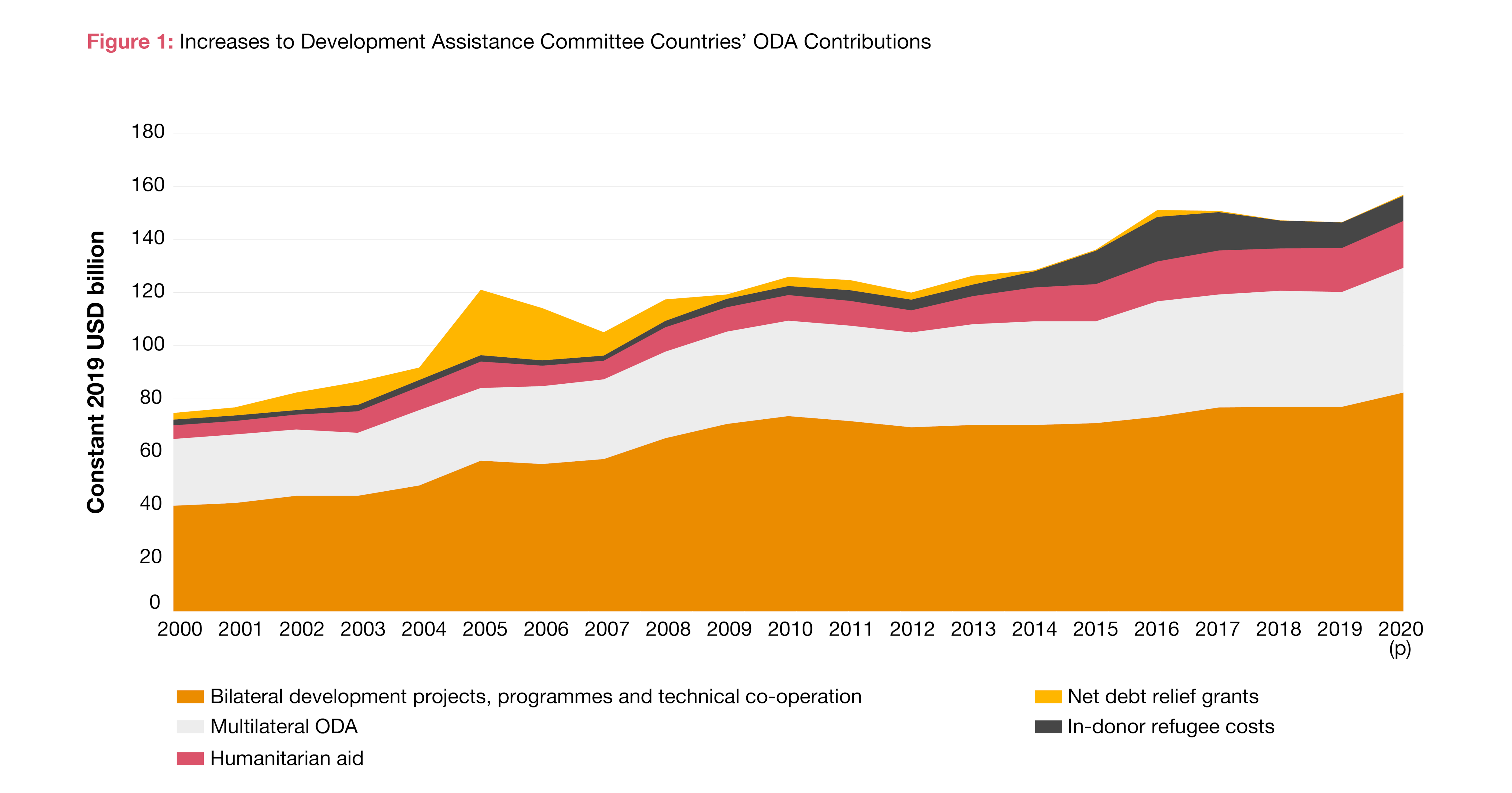

Despite record levels of Overseas Development Assistance (ODA)1, we are facing historically low levels of trust in government 2, elevated levels of economic deprivation globally and an increased disparity between rich and poor. More than ever there is a need to focus international aid on initiatives with the greatest impact, meaning funding bodies need to look for opportunities not just to donate but to become better donors.

In this report, we offer recommendations to increase the impact and effectiveness of aid and development programmes. In addition to an extensive literature review, we engaged with some of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region’s largest philanthropic education organisations operating internationally including key governmental, quasi governmental organisations, and private foundations, to understand their key concerns and focus areas. Our focus of this paper has been on education aid programmes but we hope that these insights help all regional donors and aid organisations to develop better programmes, provide more targeted support, and effectively quality assure their work.

Key considerations for effective GCC donor impact

Recent years have seen a downward trend in grant giving from GCC nations in part due to shifting donor government priorities, and, more recently, due to Covid-19 related decreases to aid budgets 4,5,6,7

In this context, how can GCC donors leverage funding to optimise their aid effectiveness, and increase visibility and learning from their programmes? What innovations in aid management should be considered to increase impact?

We propose the following framework for effective donor impact, specifically, in education development programmes.

The framework (Figure 2) positions key evidence-based programming and value for money reviews as the main pillars that interplay to enable more strategic planning, and despite inter-regional disparities on aid priorities, we advocate for activating dialogues amongst communities of practice to optimise collective regional learning and impact.

1. Strategically plan your impact

A major trend identified in our research is a lack of programme alignment to broader strategic goals, with gaps noted on two key fronts: firstly, alignment to grant recipients’ national level development policies, and, secondly, alignment to the donor country’s development policies. These gaps are paired with a historic tendency for GCC education development programming to lean towards philanthropic models for change 8,9, and an overreliance on resource provision rather than impact-based giving. For example, scholarships enable education access for marginalised groups, but these are not the end-goal, rather they are a stepping stone to workforce entry, and consequently, scholarship programmes need to align beneficiary gain with labour market opportunities for greater impact.

To maximise returns on funding, therefore, donors should clearly envision programme goals with bigger picture regional issues and outcomes in mind.

Below, we define critical planning questions to drive more transformative programming, and recommend that donors use inclusive approaches to strategic planning, i.e., planning across organisations or development agencies, and from within intended target communities:

Critical Planning Questions

What are your development agency’s specific priority areas and strategy for the next few years?

What are your development agency’s strengths and weaknesses? How do these play into planning?

What are the 'bigger picture' issues your agency is best placed to focus on? Is the strategic vision engaging with regionally compelling issues?

- What are target beneficiaries’ main barriers to enhanced life chances?

2. Create mechanisms and structures for evidence-based programming

Ideally, strategic planning will be linked with evidence bases on past and current development practice. Many of the stakeholders in our research noted that significant time is allocated to project management, with an emphasis on reviews of grantees’ monitoring reports, and little emphasis on mechanisms to use monitoring evidence to review and improve or scale up delivery mechanisms. Today’s challenges require programme design which both allows for flexibility mid-implementation, and builds in resilience to ongoing change and risk. This is possible with good ‘monitor and adapt’ mechanisms designed into delivery, monitoring and quality improvement processes.

To give an example of how this can work, one mechanism employed by the UK’s Girls Education Challenge fund manager has been to institute bi-annual review and adaptation roundtables between the fund recipients and the grant manager. In these discussions, fund recipients share proposals for adaptations alongside emerging monitoring evidence, and the final decisions are assessed for any additional evidence needed, value for money considerations, and alignment to broader development aims within the context.

Another example, at the macro level, is the commonly used results-based management approach used among many development and UN agencies, which enables organisations and donors alike to track progress indicators within various layers of impact 10. Using a results based approach at this juncture will also have reaped the benefit of years-long experience with this model, and subsequent lessons learned such as the importance of developing such frameworks inclusively and in co-creation with key developing country stakeholders 11. Given such examples, the underpinning success factor for any evidence-based programming approach is implementers’ ongoing monitoring, and quality control mechanisms to check for their monitoring data's reliability, validity, and timeliness.

3. Define and build-in strong value for money

Despite reported reductions to funding volumes, achieving value for money - defined as a desire to maximise the impact of every dollar for intended beneficiaries – was not expressed as a particular goal, nor did it carry specific importance. In light of the significant reduction of Overseas Development Assistance since 2018 by the GCC’s two biggest givers in proportion to their gross national incomes, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) (Figure 3) and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (Figure 3), the need to prioritise value for money is more important than ever.

An operating assumption to challenge here is that less funding translates to lower impact or opportunity. With a value for money (VfM) lens on project cycles, activities, and budgets, it is possible to achieve enhanced change, especially when combined with more strategic approaches to planning.

In practice, this means testing potential projects through VfM analysis that take into consideration the costs, efficiencies, equity, and effectiveness 12 of proposals. Because value for money assessments will change from one donor to another, depending on development priorities, resource envelope, and funding modality, we have formulated the following guiding principles to help assess and drive VfM:

Guiding principles to help set VfM

Define the broader development outcome and your priority for reach, depth, or innovation

Compartmentalise 'must have' activities and costs that have a high linkage with outcomes versus activities that are supportive

Benchmark programmatic costs to contextual or regionally sustainable costs – for example, looking at costs per student in relation to the average cost range in the given context

Consider big picture outcomes around equitable, economically thriving, and peaceful communities when targeting beneficiaries in acute poverty or fragile contexts – the outcomes here outweigh the likely higher costs in such contexts

Embed and prioritise evaluation, evidence, and learning into overall budget costs

Set specific budget parameters for all potential recipients around acceptable budget ranges for operational, administration, project implementation, and monitoring costs

Include the development and usage of evidence bases within project proposals or business cases to assess potential programme effectiveness, and organisational effectiveness

4. Measure your impact, and build lessons into policy and strategy

During our research, we saw little evidence of published experimental or quasi experimental evaluations arising from GCC development or aid work, in fact 75% of our research participants relied heavily on grant recipient reports for their knowledge of activities and outcomes, rather than rigorous evaluations. Evaluations offer implementers and donors alike access to a wealth of tried and tested evidence bases for decision making and long-term development planning. Though robust project evaluations may be perceived to be cost-heavy or proprietary, the return on investment from prioritising these is high as evaluations will enable more strategic budgeting based on ‘what works’, help drive sustained impact beyond the funding cycle, and enhance donors’ influence within education sector planning and policy development.

A key approach to evaluations has centered around impact evaluations which primarily use mixed research methods to test the ultimate impact of a programme. Education impact evaluations, for instance, could focus on outcomes as measured by students’ learning results at baseline, midline, and end points of the implementation. While impact evaluation models are necessary, leading thinkers in the field of evaluations have recently pointed to the necessity to incorporate process evaluation approaches to complement findings by unpacking the questions of precisely how and why the project has or has not worked toward outcomes 13. Depending on the aims of the evaluation, donors should accordingly configure evaluation guidelines that combine the most relevant approaches to test the underlying evaluation questions. Ultimately, evaluation designs should be able to target the relevancy, effectiveness, and efficiency of the programming, and furthermore, they should analyse how impact was achieved both generally, and toward various subgroups such as gender and ability groups, and other project-relevant groups such as those previously out of school, ethnic groups, or young mothers. With clear standards and design guidelines, evaluations will have an improved potential to inform long term strategic planning, and broader policy decisions around what works in different contexts.

5. Create dialogue through communities of practice

50% of participants in our research noted limited to no formal engagement with other stakeholders in the GCC education development ecosystem. This is a missed opportunity for collective impact, and could lead to duplicative or overlapping development work. Stakeholders report that there are no forums (official or otherwise) for discussion on development, and there seems to be little engagement within recipient country local education groups.

Although regional communities of practice have been limited, there have been positive shifts in the form of GCC country-led initiatives to bring together global stakeholders on the education agenda: the 2021 ReWired Summit co-organised between Dubai Cares and Expo 2020 in close coordination with the UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation witnessed the launch of key education initiatives and collaborations to fill the digital learning divide, and reinvigorated the urgency to finance and respond to learning poverty. Similarly, the 2021 Wise Summit on education led by the Qatar Foundation brought together a range of leading education experts, private sector, and policy thought leaders to discuss and pose solutions to pending problems in global education reach and quality.

Such initiatives offer important forums for collaboration, and bring together private and public sector stakeholders to solve complex issues. In future iterations, these can work more to foster inter-regional development dialogues with expectations for more coordinated efforts in recipient countries. This may have the added benefit of boosting positive visibility on the impact and learning emerging from GCC development work 14 , and support enhanced regional coordination toward sustainable development goals. Innovation in this area has led, for example, to the creation of Development Impact Bonds (DIBs) which enable collaboration across investment, private, and public sectors have the potential to significantly increase education outcomes and improve student enrollment when they are underpinned by rigorous evaluations 15.

The path forward

We are fortunate in the GCC to have a culture of care, charity and responsibility to support those in need. In this report, our objective was to focus the attention of our region’s donors on maximising the impact of their efforts. We have offered recommendations for enhancing impact and effectiveness in aid programmes, and our proposition for tighter GCC collaboration on a development ecosystem, with interwoven evidence, value for money checks, and ongoing dialogue can also pave the way for more innovative partnerships towards development financing and accountability. The viability and financial sustainability of these partnerships, in turn, require an enabling environment for adaptive programming with a strong culture of open learning and evidence during implementation, which can be achieved through the recommendations we have made above 16. With growing attention on the need for more strategic giving 17, and more key donors expressly moving away from traditional giving modalities 18, our ideas on how to do this could not be more timely. Ultimately, when donors work collaboratively and strategically on development goals, leveraging power and efficiencies toward sustainable lasting impact, we will be better able to meet the demands of today and tomorrow.