US$5 billion

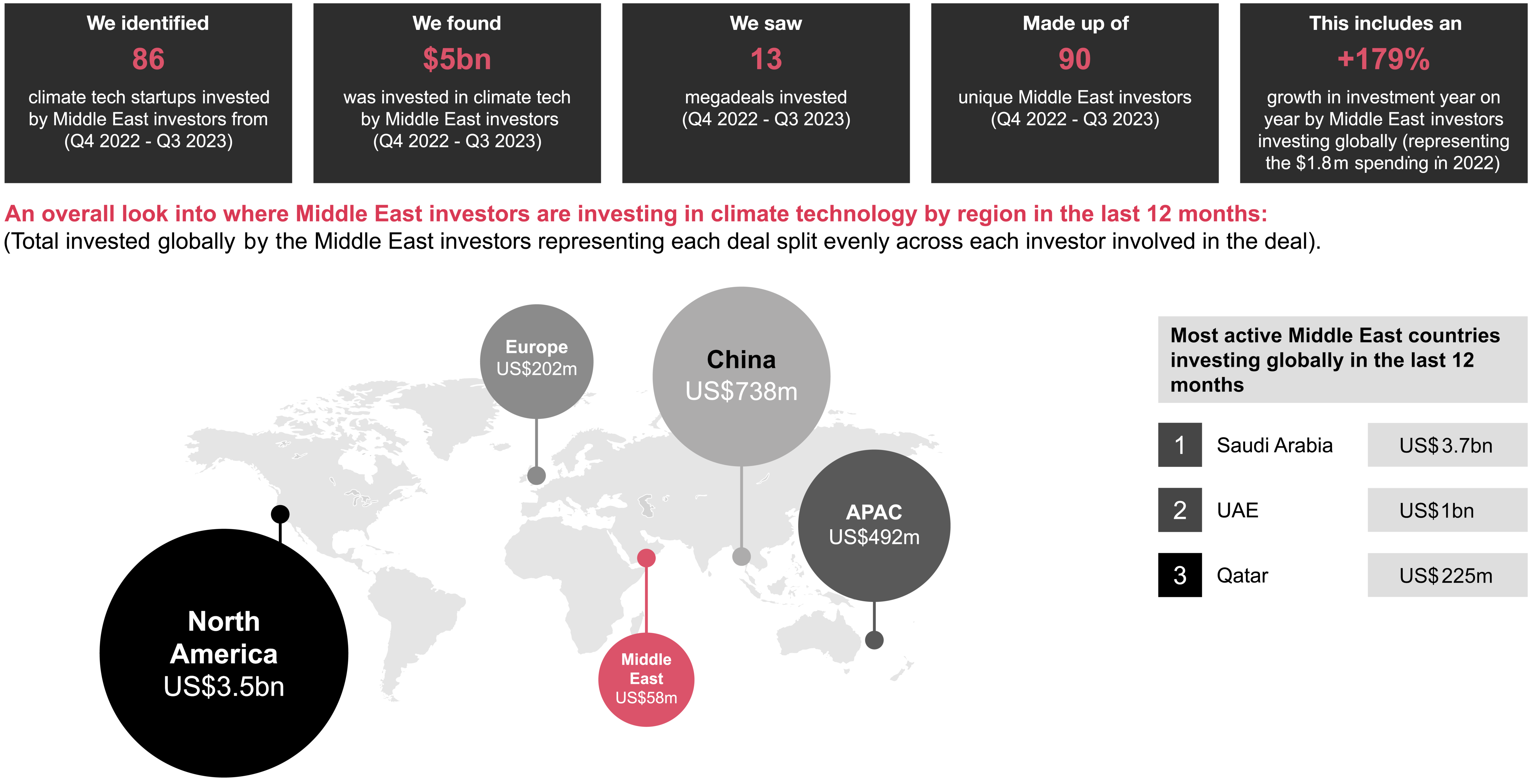

Total investment by the Middle East players in climate technology globally in 2023, up from US$1.8 billion in 2022.3 Less than 2% of this is going to innovators in the Middle East itself.

After several years of excitement about the possibilities of climate technology, the latest global data suggests that investment growth in climate tech companies - including start-ups - has cooled. But while global climate tech investment is down by more than 40% due to a lack of primary funding sources for climate tech entrepreneurs, including private equity and other leveraged investors, the Middle East seems to be showing a striking exception to this trend.

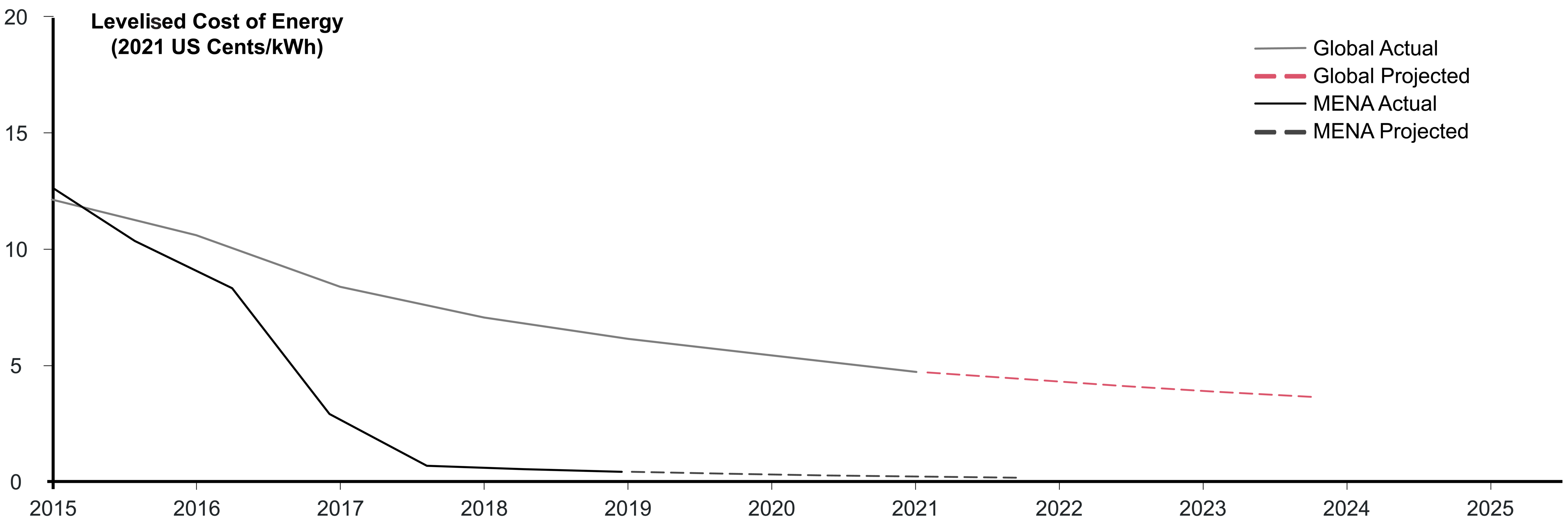

Our second regional climate technology report suggests that the Middle East players almost tripled their funding of climate tech innovation globally in the year to end-September 2023, to US$5 billion, supporting innovators in the United States, China and across Asia, and in Europe. Governments and national champions are also continuing with an aggressive build-out of renewable energy infrastructure that will accelerate the energy transition in the region, relying heavily on existing and new climate technology to drive this success.

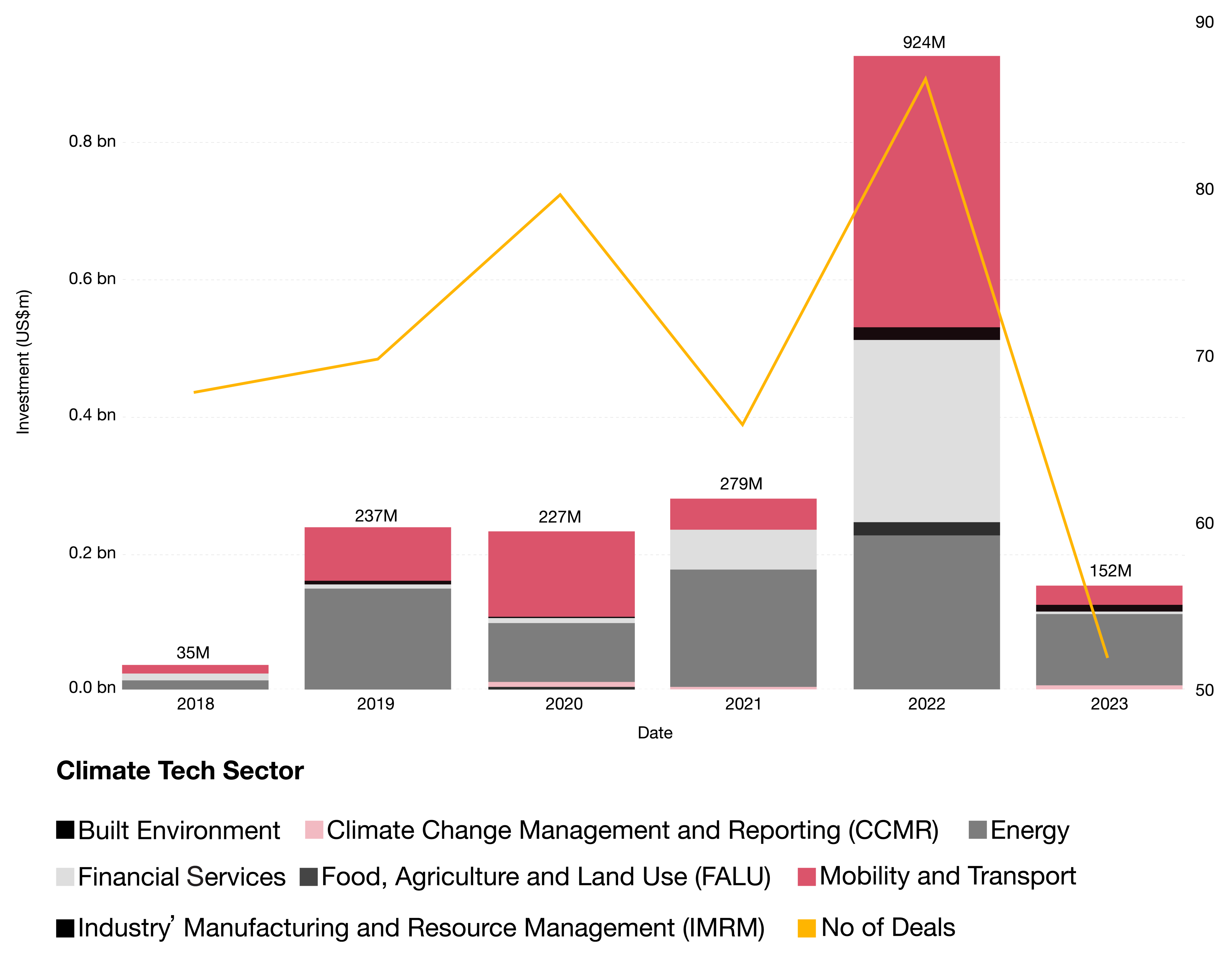

Yet amid this spending, there is one missing link: Middle East funding for climate tech entrepreneurs in the region itself. Funding for locally based climate tech innovators dropped sharply in 2023 to US$152 million – down from almost US$1 billion in 2022 – and the Middle East investors contributed just US$69 million of that total, according to our data. That is less than 2% of the amount they spend on climate tech globally.

Despite the scarcity of local funding, the energy and enthusiasm to address climate issues remain strong among entrepreneurs in our region. Alongside this year’s report, for the first time, we are launching our PwC Net Zero Future50 - Middle East, a curated list of 50 companies at the forefront of climate tech innovation in the region. The companies on this list are among the most promising innovators and entrepreneurs pushing the boundaries when it comes to reducing emissions and accelerating decarbonisation in our region.

The key messages from this year’s climate tech report are twofold. First, the journey towards achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions in the Middle East – a journey that regional governments have publicly committed to – is continuing, and gathering momentum. It needs to continue speeding up. Second, governments, national champions, sovereign wealth funds, and other stakeholders can do a lot more to build on the enthusiasm of local entrepreneurs and help develop a more robust and vibrant ecosystem for climate technology innovation in the Middle East.

By Dr. Yahya Anouti & Jon Blackburn

Total investment by the Middle East players in climate technology globally in 2023, up from US$1.8 billion in 2022.3 Less than 2% of this is going to innovators in the Middle East itself.

Total climate tech investment since 2018 into companies with main headquarters in the Middle East. Of this, US$1.1 billion invested in the past two years (including US$152 million in 2023).

Share of Future50 companies in the Middle East that were founded by female entrepreneurs. A further 32% have a mixed team of female and male founders.

Create mission-oriented funds, for example, for innovation in the built environment or the development of carbon capture technologies. Sovereign wealth funds, private investors and others could be given incentives to invest in such funds, which would need to be carefully managed and coordinated.

Stimulate demand for innovative products and services through off-take arrangements and other measures. Regulators and national champions have a critical role to play here. For the built environment, for example, regulators could develop and enforce sustainable building codes and standards that push the boundaries of innovation by recommending non-traditional materials and processes as part of their standards. These could include use of concrete reinforced with recycled plastics rather than steel, or testing new material, such as graphene concrete. National champions could open the doors to smaller entrepreneurs by building labs and guaranteeing a predictable volume of off-takes for strategic products, for example, products that use green hydrogen. They could also look to build their own domestic network of suppliers, giving priority to the most innovative regional start-ups.

Incentivise private investors to fund start-ups and play a greater role in helping find technological solutions. Various incentives could be applied here, including subsidies or tax breaks, but the biggest lift to private capital in a start-up ecosystem would be comprehensive measures that reduce investment risk, particularly a solid system for off-takes, combined with a transparent path for investors to exit their investments after several years with an adequate return.

Empower and encourage innovation. The Net Zero Future50 highlights the entrepreneurial energy in the region, and more can be done to encourage that, including in the higher education system, which could spawn incubators and accelerators and develop new curricula focusing on environment-related skills, such as climate engineering. Innovators will need markets for their products and services, which is why the focus on demand is so critical for stakeholders.