{{item.title}}

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}

07/02/22

Disruptions presented by climate change, social effects of an aging population, and social polarisation are among the issues that have taken centre stage in the aftermath of the pandemic, as outlined in World Economic Forum (WEF)’s Global Risks Report 2022. These factors are expected to have a serious impact on economies and livelihoods in many countries around the world in the next ten years.

The question is what actions are being taken to combat this disruption to be fit for purpose, and how can businesses answer the call to address some of society's toughest problems.

These issues are certainly keeping organisations and policymakers on their toes i.e.

Taking action today for tomorrow, whilst making sure that future generations have the ability to meet their needs,

Transparency on actions taken, i.e. to demonstrate measurable (where possible) outcomes.

Sustainability is a key pillar in any strategy to deliver growth and remain relevant amidst the accelerated interest in climate change, sustainable value chains and responsible investments. In this blog, we consider environment, social and governance (ESG) issues via a tax lens, and delve into each aspect of ESG in our upcoming blogs.

Tax revenue is the lifeblood of a country, and its contribution enables us to support the capital needs of the country, including initiatives supporting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened focus on the concept of “fair tax”, and its inclusion in climate, social and economic strategies for more resilient business models. Investors are demanding greater transparency around disclosures on total tax contributions and how businesses support these strategies.

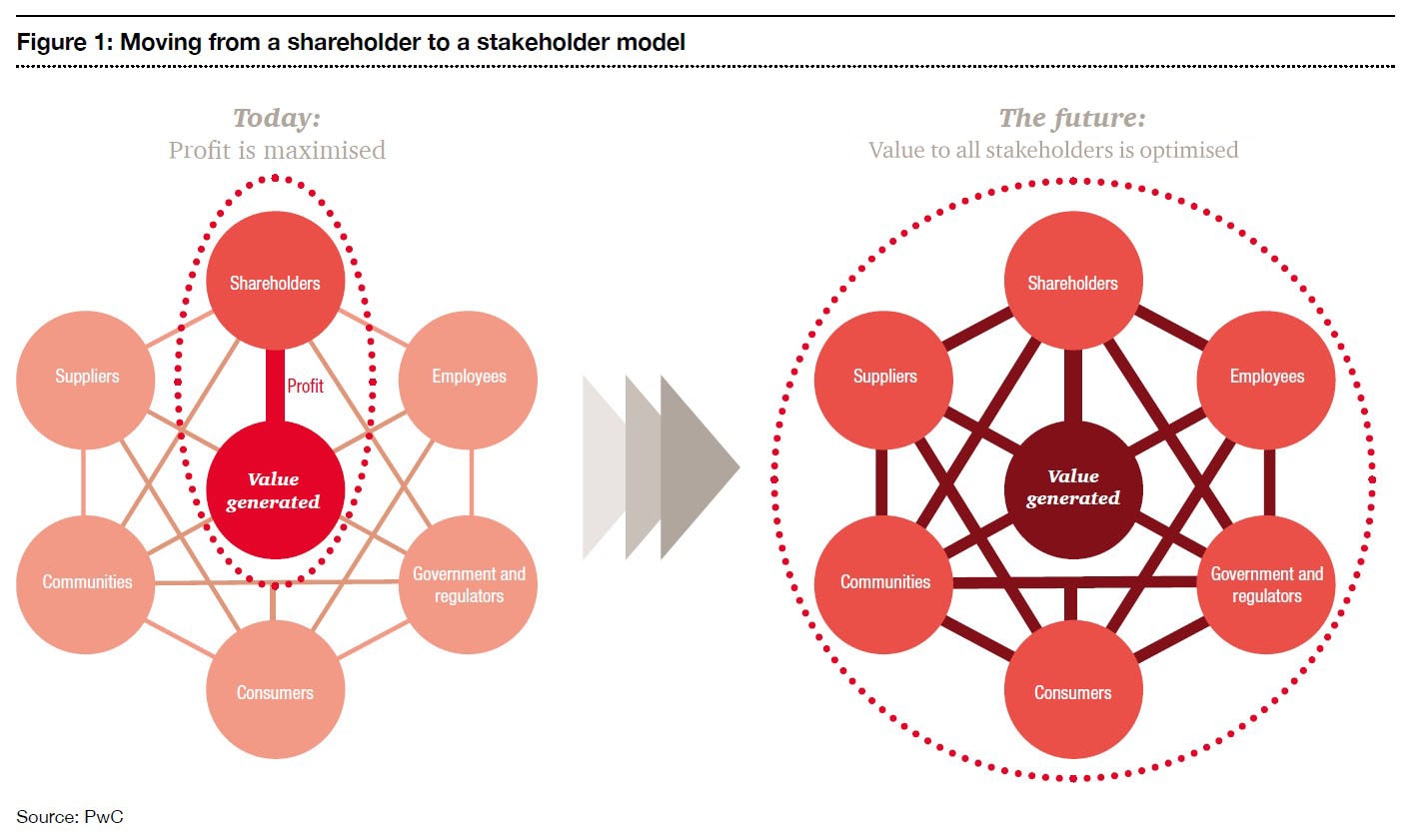

While profit generation continues to be a ‘given’, there’s been more emphasis on value optimisation (see diagram above). Companies are asking themselves how they can adequately balance the needs of all their stakeholders. For instance, closer attention to collection of tax revenue (and whether channelled appropriately) triggered by the aggressive strategies of some of the world’s tech giants and industries who have captured market share during this time. Increasingly, governments and investors are relying on tax disclosures and ESG profile assessments, amongst others, for responsible investment decisions to deliver long-term value and to ensure that fair taxes are collected to support a country’s sustainable development including healthcare, education, infrastructure which ultimately benefits everyone, not only shareholders. This highlights the importance of the tax intersection with ESG which has led to efforts by governments and businesses to reinvent, invigorate and pivot their tax strategies to stay relevant.

Tax authorities have been calling for cooperative compliance and increased disclosure on management of tax obligations via “country by country reporting” and other country specific requirements. A few that come to mind are Malaysia’s Fiscal Responsibility Act [proposed], Medium Term Reporting Strategies, Australia’s Justified Trust Programme, and Singapore’s pilot programme for development of a governance framework for income tax.

A common thread in these requirements is detail on how tax risk and obligations are managed by businesses to ensure fair taxes are being paid. This has resulted in more guidance on such disclosures, e.g. Bursa Malaysia’s Tax Governance Guide, Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI) 207 and other sustainability indices, which reinforce the tax perspective in the “Social and Governance” dimensions in assessment of ESG practices/strategies. For instance, business disclosures on tax governance and risk policies adopted and total tax contributions paid enable insights on their contributions to the country’s capital needs, support responsible investment decisions, or enhance visibility on the effectiveness and outcome of “green” subsidies or incentives provided, amongst others.

Countries are at different stages of ESG adoption, which impacts their policies on carbon levies/ taxes. Discussion to level the playing field with an international carbon pricing floor at the recent COP26 may be helpful, provided the international community is willing to commit (akin to recent adoption of the OECD’s Pillar 2 obligations). Hence, businesses should monitor how this additional revenue impacts policies and the regulatory landscapes where they have a presence.

Jumping on board the green bandwagon with “carrots” (tax incentives, subsidies) and “sticks” (carbon taxes) to address the ‘environment’ dimension of ESG has resulted in many businesses reviewing their models/arrangements and investments more extensively. The rise in businesses and countries who have set out net zero commitments, has resulted in many having to revisit their supply chains. For instance, the variance in adopting regulations around carbon emissions has impacted businesses’ pricing models. This may also impact their profiles to obtain financing, amidst increasing investor and financial institution focus on ESG adoption in potential investee companies.

More businesses are also considering the glaring absence of disclosures on tax in their comprehensive sustainability reports (that outline extensive details on reduction in carbon emissions, cutting edge environmentally-friendly technologies and how they give back to communities, etc).

In 2019, the US Business Roundtable (BRT) discussed the importance of sustainable value creation for stakeholders and also acknowledged the importance of tax to support the orderly function of civil society, which accompanied the release of their new “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation”. The statement was signed by 181 CEOs including those from the ‘B Team’, a coalition of business leaders advocating sustainable business practices, and have committed to lead their corporations for the benefit of their stakeholders (namely, customers, employees, suppliers, communities and shareholders). Many of these businesses have adopted international reporting standards to support their reporting/disclosures of actions taken to crystallise their commitments. This includes an increasing adoption of the GRI 207 on tax disclosures (with effect from 1 January 2021), which is the first global standard for comprehensive tax disclosure at the country-by-country level.

Whilst the “carrot” and “stick” approach to taxation has proven to be effective in encouraging sustainable behaviour, it has been country-specific. Here are some actions being implemented/proposed by Malaysia in each ESG dimension.

“E” - Environment, minimising the impact of an organisation to nature |

Initiatives to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) or other greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions including:

|

“S” - Social, contributions by an organisation to promote fairness in society |

Contributions to promote trust, welfare and equality in society, product safety and data privacy and security. For example:

|

“G” - Governance, processes for decision making, reporting and ethical behaviour |

Focuses on quality and scope of reporting and accountability. This includes tax transparency, for example:

|

Malaysian public listed companies are required to disclose management of material economic, environmental/social risks and opportunities via a sustainability statement in their reports. Whilst ESG reporting is not yet explicitly defined - we already see underlying tones through requirements of integrating sustainability considerations in corporate governance, strategies and decision making by Boards. In addition, Bursa Malaysia, indicated that businesses that adopt GRI on disclosures are considered “above average” and issued guidance on their expectations for Tax Governance disclosures (October 2021) for “large” companies1 (defined). Tax transparency is also a key theme determining the ESG ratings of companies on the FTSE4Good Bursa Malaysia (F4GBM) Index. Hence, businesses should consider:

What is the impact of ESG to their business models, e.g. supply chain, incentives/subsidies available, carbon taxes/pricing policies

Whether the ESG policy in place is aligned enterprise wide, i.e. across business units, internal functions (including tax)

Availability and access to data for ESG reporting, e.g. total tax contributions

Get in touch if you would like to delve deeper into any of the aspects covered in this blog.

1 “Large companies” are those on the FTSE Bursa Malaysia Top 100 Index or those with a market capitalisation of RM2 billion and above at the start of the company’s financial year.

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}